A (not so little) bird is telling us...: Thinking with geese on the York University Campus

By Seema Shenoy

Towards the end of the summer in 2015, having just arrived from India, I made my

A few geese cool off at the water fountain in front of Vari Hall. Photo credit: L. Anders Sandberg

way to the York University campus for the very first time, to see the place where I would be spending the next two years in the Master of Environmental Studies program. The fall term hadn’t begun yet. When I got off the 96A bus, the few people that were on it quickly disappeared into the recesses of air-conditioned buildings and I was left alone to take in my first view of the campus. I looked around and couldn’t see another (human) soul outside, but a gaggle of Canada geese was occupying the fountain, perhaps unintentionally affirming the purpose of the YorkU “Commons”. With my map in hand, I made my way down Campus Walk, around Ross Building and onto Library Lane, briefly stepping off the path to walk around a couple of more geese that had taken up its entire width. As I made my way towards the Health, Nursing and Environmental Studies building, I came upon a second group basking in what used to be open space but has now materialized into the New Student Center. Having never encountered wild geese before, I thought I was witnessing a rare event and assumed that it was the absence of humans that the geese were taking advantage of. When I returned a couple of weeks later to join a group of students on the conventional campus tour, I realized that my first impressions were wrong. As we walked through the campus, now abuzz with activity, the presentation given by our enthusiastic tour leaders was frequently interrupted by our own encounters with geese. It wasn’t the geese that initiated these interactions, but the other students who wanted to stop and take photographs of (and the more daring of the group, selfies with) the geese.

Visiting one of our Neighbours: Walking the Black Creek Pioneer Village Site

By Jesse Thistle

The entrance to Black Creek Pioneer VIllage

Black Creek Pioneer Village, a re-creation of a white settler farming settlement in southern Ontario from the 1860s, is one of York University’s prominent neighbours. In 2013, the Village reported it attracted 145,000 visitors per year. It even has its own new subway stop (as of December 2017), named Pioneer Village, which is expected to draw even more visitors to the site. The Village often hosts retreats and conferences of Faculties and departments at York University. In 2016, for example, Osgoode Hall Law School held a meeting there on its Strategic Plan 2017-20, and part of it was a discussion on its response to the recent Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, the report that seeks to address the injustices faced by indigenous peoples over the years. Yet the indigenous presence in the Village is largely missing. This is what prompted the following, a story reprinted from the Active History website (slightly edited and complemented with photos), and told by Jesse Thistle, a Metis-Cree scholar, who recounts a personal story about his experience in dealing with the indigenous absence in the village.

Now You See It, Now You Don’t: Looking for the Tree of Heaven at Founders College

By Darren Patrick

Who arrives?

Who invades?

Who is welcome?

Who is not?

When does a plant become a weed?

Since 2012, I have developed an unlikely relationship with Ailanthus altissima, a species of tree more commonly known as the Tree of Heaven. Tree of Heaven is one of the most “successful” global plant species. It lives on every continent except Antarctica and thrives in urban areas. Moreover, it is the evocatively titular tree of Betty Smith’s 1943 novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, which recounts the struggle and coming-of-age of an Irish-American in early 20th Century Williamsburgh, Brooklyn. The plant’s thriving in abandoned lots frames the book’s stories of struggle and growth as part of a marginalized immigrant community. The Brooklyn neighbourhoods at the center of the book eventually passed to non-European immigrant communities. Now subject to gentrification, the neighbourhoods are locations of intensifying cycles of change and resistance. Amidst it all, the tree, as in many places, continues to grow.

Safety Phone at Central Square

By Michaela McMahon

This safety phone in Central Square is one of the 35 emergency phones located on campus. The bright yellow colour and spinning blue light are supposed to make these phones easy to see…but how often do we look up from the phones in our own hands as we walk across campus? And if we wanted to call for help or sound an alarm, wouldn’t we just use the York U Safety app for that?

In many ways, these phones are symbols of changing technologies and changing conversations. They stand for what has been the dominant conversation about safety on campus for decades: a conversation where, when we talk about promoting “safety”, we know what’s really meant is “avoiding sexual assault”. This is a story that we have to think about more closely.

Vari Hall: A public or private space?

By L. Anders Sandberg

Adorned with yellow brick and two lower rectangular structures extending from its sides, Vari Hall appears to be a well-designed and extraordinary space. As I enter the building I am engulfed by a cylindrical-shaped hall and stories echoing of its outer walls. The building was constructed in 1992 and named after one of York University’s benefactors George Vari (1923-2010)—a Hungarian refugee from the revolution in 1956 who made a fortune in the construction industry—and his wife Helen. Its sleek post-modern design was intended to provide the sprawling suburban campus with a more urban aesthetic, revamping its image as a poor cousin to the University of Toronto. Of the three interconnected buildings, the Rotunda is most eye-catching; it is also the centre of frequent social and political debates.

The Ross Building Ramp and Terrace: Curse or Promise?

By L. Anders Sandberg

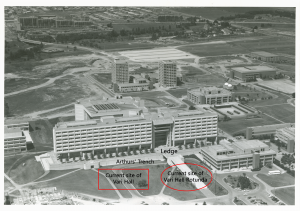

Some time ago I conducted a campus tour for a group that included a couple of senior faculty members at York. When walking across the ledge leading over the narrow empty and largely vacant space between the Ross Building [originally called the Ross Social Sciences and Humanities Building] and Vari Hall, the faculty members pointed out that we were crossing Arthurs’ trench, named after Harry Arthurs, the president of the University who spearheaded the effort to build the Hall in the early 1990s.

Michael G. Boyer Woodlot: A living place of symbiotic stories: Exploring woodlots as place-makers of culture, time and resistance

By Adrina Bardekjian

First Nations peoples’ fires burnt the forest now known as the Michael Boyer Woodlot for centuries. The fires were likely used to provide room for the three sisters (squash, beans and corn), for spiritual ritual, and fostering community. European settlers’ plows and axes later ruptured the same earth, surrounding root systems and felled neighbouring trees to establish fields for cash crops. However, the forest maintained some of its original ecological and hydrological roles during the settlement and farming era. After the property was purchased from the Stong Family, the university started its rapid construction phase in the 1960s. This is the beginning of the Michael Boyer Woodlot narrative—a series of complex stories which cast the woodlot as a place of study and student refuge, an obstacle to development and a management unit.

Scott Library: A Place for Books or People?

By Dana Craig

I love the library! I started working as a student assistant in Scott Library in the mid-1990s and then started working full time in 2000. I sometimes feel that I have walked the hallways and stacks for a very long time, however, in reality, there are many library staff members who have worked here for 30 and even 40 years. During this time span, technology, diverse learning styles and shifting campus culture has transformed the library and the role of the librarian.

HNES Native Species Garden

By Michael Classens

You might call the HNES Native Species Garden a campus naturalization project—designed to make the campus more ‘natural’. The corollary to this, of course, is that the campus was (maybe still is) too ‘unnatural’. And I have to admit, the tactile contrast between the concrete campus surrounding the HNES garden, and the soft mulch within it, is stark. My feet unanimously prefer the latter. Yet this is only the start of the incongruousness between the garden and the campus beyond. What I see, smell and feel is all noticeably different inside the garden than beyond its borders. Outside the garden I see mostly buildings and turf grass, within it, there are dozens of native species of plants, flowers, shrubs, grasses, a few trees, and even a couple of groundhogs. And then, as though purposefully spoiling the tidy conceptual and sensorial division between the ‘natural’ garden and the ‘unnatural’ campus, I see a duck waddling down a campus sidewalk.

Stong Pond: What role does it play in managing the storm water on campus?

By L. Anders Sandberg

On August 20, 2005, the day after a major hurricane hit and flooded York University and its surrounding community, I walked some of the stream valleys southwest of the campus to examine the damage. The hurricane had had a devastating impact. There was litter everywhere - branches, leaves, and garbage that the flood had thrust downstream. The walls of a storm water pond had crumbled, exposing the broken culverts that carried the water from the pond to a neighbouring stream. But the most serious damage occurred at Finch Avenue where the water and debris laden Black Creek had blocked a culvert, creating a dam that put so much pressure on the road that it was washed out. When I looked at the trees above the blockage, I noted a mud-line about 2.5 metres high that gave an indication of the volume of water that had pooled behind the blockage. What caused this disaster?