When a 2005 hurricane flooded the campus and washed out parts of Finch Avenue just south of the campus, the campus’ storm water pond was confirmed as inadequate (it could not hold the water of a major hurricane), and it was therefore rebuilt and expanded. But was it really necessary to expand the pond? Photo by L. Anders Sandberg

On August 20, 2005, the day after a major hurricane hit and flooded York University and its surrounding community, I walked some of the stream valleys southwest of the campus to examine the damage. The hurricane had had a devastating impact. There was litter everywhere - branches, leaves, and garbage that the flood had thrust downstream. The walls of a storm water pond had crumbled, exposing the broken culverts that carried the water from the pond to a neighbouring stream. But the most serious damage occurred at Finch Avenue where the water and debris laden Black Creek had blocked a culvert, creating a dam that put so much pressure on the road that it was washed out. When I looked at the trees above the blockage, I noted a mud-line about 2.5 metres high that gave an indication of the volume of water that had pooled behind the blockage. What caused this disaster?

In a one-hour period 103 mm of rain fell on the area. This constitutes an extreme weather event and significantly exceeds the 53 mm of rain dumped when Hurricane Hazel swept through the Toronto region in 1954. Like Hazel, this recent hurricane caused serious damage. At Finch Avenue there were two broken gas mains, one broken water main, one broken maintenance hole, backed-up storm sewers, over 4,200 flooded basements and a 5-month disruption in traffic, causing an estimated $45 million damage to local residents and businesses.

Since that walk along Black Creek, I have asked many questions about the hurricane. Was it, as one city official suggested at the time, an act of God? Or was it an unavoidable natural disaster? Or was it a result of poor planning on the part of people? Given the more extreme weather patterns bound up with climate change, shouldn’t the City have known better? And if it had known better, what could have been done to avoid the damage? Later that same City official told me that, unfortunately, there were no forensic studies focused on uncovering the causes of the Finch Avenue washout because city staff was too busy cleaning up the mess.

Consequently, I began to ask these questions in the context of my own institution, York University. I sought to identify its responsibility, if any, in the disaster at Finch Avenue. My investigation led me to believe that both the City and York University could have done, and could do much better, in managing the storm water on campus.

My interrogation of campus storm water management began well before the Finch washout, namely, at a meeting on campus planning where the university planner presented a project to expand Stong Pond, the storm water pond on campus. A storm water pond is a retention pond for storm water that is aimed to prevent floods. I learnt at the time that Stong Pond was inadequate as a storm water pond. It was too small to handle the storm water situation on campus. It was always full, and therefore incapable of handling the sudden huge volume of water that may emanate from a major storm. Yet, as we looked at Stong Pond on a map of the campus, I asked myself what had caused the Pond to be considered inadequate in the first place.

What if Stong Pond is a symptom of a larger problem rather than a problem itself? Didn’t the activities occurring in the “headwaters” of the pond, that is, the areas that drain into the pond, have something to do with its “inadequacy”? This is, after all, where an extensive hard-surfacing of the watershed has occurred. I raised these points at the meeting and received some sympathy from the University Planner. He has since left.

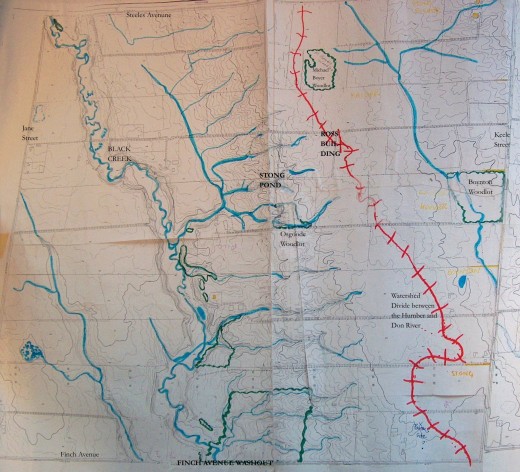

After the meeting, I began to dig deeper into the wider development context of the Pond. I became convinced that the University’s approach to development was consistent with a dominant narrative that holds humans above nature, and assigns to them the right and duty to control and manipulate the natural world in order to maximize buildable surfaces, profitability, and a high-consumption lifestyle. At York it started with a change in the configuration of land on the campus. I learnt that originally, almost half the campus area drained into the Don River Watershed in the east and the rest of the campus drained into the Humber River watershed. But then an artificial sewage network was created in order to accommodate campus development, making all the storm water flow into the Humber watershed. The new storm water sewershed consisted of a series of drains and subterranean pipes and hard surfaces that channeled storm water into Stong Pond and further into Hoover and Black Creek, the Humber River, and eventually Lake Ontario. The central part of the system is the York University Storm Sewer, built circa 1963, a round concrete pipe that is maximum 1.80 meter in diameter and then progressively smaller. It begins in the vicinity of Winters College, then passes under Vari Hall and the Ross Building until it reaches Strong Pond. Urban explorer Michael Cook provides some spectacular photos of the storm sewer at his website The Vanishing Point.

Another set of storm water ponds have since been constructed south of Stong Pond in conjunction with the building of the Rexall Tennis Centre and the Tribute Homes subdivision. This system of drains, pipes and ponds has allowed for the massive development of the campus. Artificial interventions such as the creation of ponds and sewersheds, used to facilitate the development of the University, have become so normalized that they appear on maps of the Don and Humber watersheds. Many perceive this water management approach as being a progressive and effective solution.

Watershed divide between the Humber and Don Rivers in the 1950s before the university was developed. Topographic map and sketches courtesy of Helen Mills, founder of Lost Rivers Walks.

Watershed Divide between the Humber and Don Rivers as mapped by the Toronto Region Conservation Authority. The watershed divide has moved a considerable distance to the east and is in fact a sewershed divide. Detail from map entitled Which watershed do you live in? produced by the Toronto Region Conservation Authority, no date

And then the hurricane of 2005 hit and university managers had their thesis of Stong Pond confirmed. See, it was indeed inadequate, it had overflowed causing extensive flooding on the campus, though there was no acknowledgement that it may also have contributed to the mass of water that washed out Finch Avenue. I felt the Pond had got a bad rap. There was no questioning of the development path of the University. And to make matters worse there were also claims that the pond had become severely polluted and contained dangerous substances and garbage. In my view, the hurricane was an inciting incident, which empowered university officials to move forward with their longstanding proposal to expand the pond rather than interrogate the rate and type of campus development.

I began asking more questions and conversing with other physical features on campus. What other solutions to storm water management exist? These questions lead to an exploration of how the University can employ a more environmentally sensitive building and planning approach to its development.

One thing that spoke to me was, strangely enough, a sculpture, Mark di Suvero’s Sticky Wicket, which sits north of Stong Pond. It inspired me to think about an alternative way of looking at storm water management on campus. The large steel beams that constitute di Suvero’s sculpture plunge delicately into the ground rather than sit on a concrete pad; this allows for rain and snow to gradually percolate into the soil, making the sculpture and the land connected rather than separate.

The Sticky Wicket by Mark di Suvero. Does the sculpture inspire different ways of looking at storm water management? Photo by L. Anders Sandberg.

Taking a cue from the Sticky Wicket, a different set of measures can be considered, including stopping hard-surfacing of the ground and even reversing the existing pattern, exposing the earth as an agent that can absorb storm water. The sculpture also invited the use of permeable hard surfaces, through which storm water can percolate, and building wetlands that attract storm water. The planting of more trees, day-lighting buried creeks, constructing more effective green roofs on the campus (there are already two), and disconnecting downspouts are other methods that can be applied to retain and accommodate storm water on campus. Such measures can not only save on building up and replacing an old and aging sewage system but also make local areas take responsibility for storm water flows that are bound to increase and become more unpredictable in an era of climate change.

One need not go far to find support for such measures. The City of Toronto’s Wet Weather Flow Master Plan operates on the principle that “wet weather flow will be managed on a watershed basis accompanied by a hierarchy of solutions starting with “at source”, followed by “conveyance,” and concluding with “end-of-pipe.” On the campus, the focus on the storm water pond as the central focus for addressing the storm water situation takes away from the problems and solutions “at source.”

This is the place where the most of the campus’ storm water pipes converge and deposit its content into Stong Pond. Photo by L. Anders Sandberg.

Based on this more holistic view of looking at the hurricane I took a position against the expansion of Stong Pond and became an advocate for broader watershed approaches to tackle the storm water situation on campus. I went to official planning meetings and made my point known. I penned an article for a campus newspaper with my colleague Jenny Foster protesting the expansion of the pond and road structures south of the campus. I made some attempts to rally the troops but with poor results.

I had a few sleepless nights and cringed when the bulldozers dug into the earth to expand the pond. In the weeks following I wondered whether the claims that the original Stong Pond was polluted were exaggerated and a mere excuse for its expansion. I imagined that the original Stong Pond had built up its own ecology that harboured its own unique animals and plants who we didn’t know about.

The bulldozers are taking a rest in re-building Stong Pond in October 2007. Note the ring-billed gulls who are feasting on the exposed goodies unearthed by the machines. Photo by L. Anders Sandberg.

In 2006 when one of our doctoral students in the Faculty of Environmental Studies found a rare yellow-spotted salamander in the grass by the pond on a rainy day, I felt my position was confirmed. I also found inspiration in a poem that Ottawa poet laureate Cyril Dabydeen had penned in praise of the pond while sitting on its banks.

By Stong Pond watching seagulls [they are in fact ring-billed gulls, my comment LAS] this summer,

The wind howling, a farmhouse refusing

To be blown away; water furling,

As a goose transforms itself

Into a loon. So easily we laugh,

Lying on the grass with the sun

Between your eyes forming

Parallel lines.

Unfortunately, the old Stong Pond did not prove as resilient as the farmhouse that sits across the road from it. But the geese still return, and so do I.

So what is your position? Is storm water management mainly an engineering activity that is subservient to development, where storm water is channeled into subterranean pipes, ponds and channelized streams to end up in Lake Ontario? Or should it be a locally-based method where the local places take responsibility for its own storm water though limiting development and letting the land and vegetation serve as absorbers of storm water? How do we balance engineered and natural methods to storm water management?

Sources:

- Dabydeen, Cyril, “Stong Pond, York University,” Arc, 51 (Winter 2003), 85.

- Ontario. Ministry of the Environment. Climate Ready: Ontario’s Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan (2011-2014). February 2012, accessed March 20, 2013, http://climateontario.ca/doc/workshop/MVCWorkshop/DesRosiers-ONeill-MVC_Workshop.pdf

- Reeves, Wayne and Christina Palassio, HTO: Toronto’s Water from Lake Iroquois to Lost Rivers to Low-flow Toilets. Toronto: Coach House Books, 2008.

- Sandberg, L. Anders, “Promoting Environmental Education at the University: The campus as a sticky wicket,” Our Schools/Our Selves, 19, 1 (Fall 2009), 113-120.

- Sandberg, L. Anders and Jennifer Foster, Stormy Weather: On Hurricanes, Water and Hard Choices at York, Critical Times, 3, 5 (April 2006), 6-7.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.