Some time ago I conducted a campus tour for a group that included a couple of senior faculty members at York. When walking across the ledge leading over the narrow empty and largely vacant space between the Ross Building [originally called the Ross Social Sciences and Humanities Building] and Vari Hall, the faculty members pointed out that we were crossing Arthurs’ trench, named after Harry Arthurs, the president of the University who spearheaded the effort to build the Hall in the early 1990s.

Before Vari Hall was built, there was a huge ramp in its place. The ramp started from the parking lots at ground level and ended at the ledge and the elevated pedestrian-based terrace of the Ross Building. From there, university members could look out over the surrounding buildings, the ring road, pedestrian pathways, greenspaces, farm fields and parking lots of the campus. They could also enter the Ross Building and a couple of other buildings connected to the terrace, the Scott Library and the Curtis Lecture Halls.

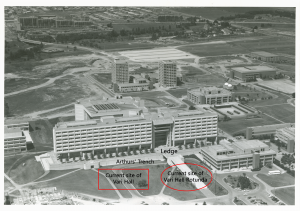

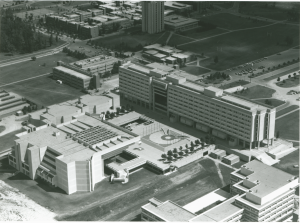

The Ross Building, the ramp, and the east side of the terrace with the approximate locations of the future Vari Hall Rotunda and Vari Hall bounded by a red line. The future Arthurs' trench and the ledge between Vari Hall and Ross Building are also marked on the photo. Photo courtesy Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections.

Arthurs hated and cursed the ramp. The story that is told is that he and one of his colleagues were sitting in his office on the 9th floor one winter morning after it had snowed. They decided to check for footprints on the ramp by the end of the day and found none. The observation confirmed Arthurs’ opinion that the ramp was “ugly, useless and totally misconceived” and his resolve to remove and replace it with Vari Hall. In the process, however, he neglected its symbolic and other utility functions, including the activities that took place underneath it and the emotional attachment it held to many members of the campus (Ancinelli, 2009).

The Ross ramp was demolished in 1989 to give way to Vari Hall. Photo courtesy of York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collection (F0091), ASC00277.

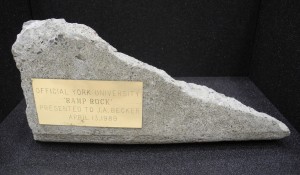

Memorobilia from the Ross Ramp. Ramp Rock presented to J.A. Becker. Object held at York Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collection. Photo courtesy the author.

The ear-rings were made from ramp rubble by Faculty of Arts student enrolment advisor Karen Hecker. Objects held at York Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collection. Photo courtesy the author.

I write about Vari Hall in a different story of the Alternative Campus Tour. Here I focus on the Ross Building ramp and terrace and their physical and symbolic significance. I will try to make the case that these spaces have some promise and endearing qualities that should be celebrated, remembered and perhaps even serve as an inspiration to do things differently.

I like the term trench as a descriptor of the space between the Ross Building and Vari Hall. It is not only a good term for a physical but also a metaphorical space, a space that separates two different periods of the university, and the loss of a set of sentiments, principles, and goals associated with a past era.

The Ross Building was built with public money, opened in 1968, and named after a public figure, Murray Ross, York University’s first president. It is designed in a modernist-brutalist style, a rectangular concrete slab built to form the focus of the campus. Brutalism does not sound very people-friendly but it was in fact part of a post-war movement to provide inexpensive housing to the masses, but also architects with large budgets adopted the style because of its ’honesty’ and sculptural qualities, and even, perhaps, its uncompromising anti-bourgeois nature (Wikipedia, 2014). To me, it is an illustration of the enlightenment university, the university that fosters citizenship and a broad-based liberal arts education. Vari Hall, by contrast, was built in a postmodernist style in 1992 and named after George Vari, a wealthy businessman who built and sponsored part of its construction. It is part of the neoliberal or enterprise university, the university where students are consumers and an education is conceived of as a commodity that yields a good job.

As I cross Arthurs’ trench towards the Ross Building I imagine what it would have been like to walk up the ramp to the entrance of the terrace that was designed to be the “grand door” to the university.

Arthurs’ trench with the ledge in the distance connecting the Ross Building and Vari Hall. Photo courtesy the author.

I would have started my walk from the huge parking lot, then onto the ramp and ended up in the middle of the eastern section of the Ross Building, facing an exposed row of rough-cast piers facing the ramp. Architectural historian Philip Beesley described the ramp as “a great open stoa [public walkway]” leading up to “a primordial temple front recast as an institution for the Age of Aquarius in the 1960s”(2007: 264). As I look at the face of the temple, which is still there, I read a statement by Murray Ross inscribed in the concrete:

"We at York must give special emphasis to the humanizing of man, freeing him from those pressures which mechanize the mind, which make for routine thinking, which divorce thinking and feeling, which permit custom to dominate intelligence, which freeze awareness of the human spirit and its possibilities …"

The statement uses sexist language and is part of the vision of a white, male, middle-aged academic administrator who largely associated with similar looking and like-minded people. Yet it is also part of a laudable goal, representing a time when the university was seen as a liberal arts institution, a space of infinite possibilities, and a place where students received a general education in their first two years of study and then entered a disciplinary stream. It was an education that promoted critical thinking amongst students and that prepared them to be engaged citizens rather than mere professionals or workers. It was also a time when Canadian universities transformed from institutions for the elite to ones of the masses, and enrolment at York University sky-rocketed.

The “primordial temple front” of the Ross Building. The statement of Murray Ross is located at the bottom concrete bar which is part of glass-walled corridors that connect the south and north end of the building. Photo courtesy the author.

As I look at the southern wall that flanks Ross’ statement, I see sixteen poles. It was here that the flags of the university and colleges were displayed during convocations. Graduates would then have been reminded of York’s public mission and symbols. The convocations then spilled into the western section of the terrace and the stage for the ceremony was placed up against one of the walls of the Scott Library.

Convocation held on the Ross terrace some time in the 1970s. The podium is located against the wall of the Scott Library and the west side of the Ross Building is in the background. Photo courtesy of York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collection, ASC 19503.

Hold on to your hats! Convocations were often windy affairs on the Ross Terrace. The photo is showing the convocation podium against the wall of the Scott Library. Photo courtesy of York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collection, ASC19502.

By contrast, convocations are now held at the corporate-named Rexall Centre, where Tennis Canada has leased land from the University and built a complex that hosts its administrative staff and the annual international Rogers Cup Tennis Tournament. The terrace, I feel, is a place crying out to be reclaimed and celebrated. One day, I think, I would like to play a tennis match there.

The large area to the west of the Ross Building was confirmed as a centre point of the campus by promotional photos of the university in the 1970s, photos that are now replaced by various perspectives of Vari Hall.

An oblique air photograph of the York University showing the Ross Building terrace as the central focus of the campus. Photo courtesy of York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collection, AC19501.

The first thing that I confront as I emerge from passing under the Ross Building is an opening in the terrace that houses a garden that is part of the Central Square Complex of walkways and space under the terrace. The garden contains a group of trees at the western end and a place of tables, parasols (in the summer) and a fountain at the other end. In the past, the garden could be reached by two sets of stairs from the terrace but they were, just like the ramp, removed a number of years ago.

The Central Square Garden seen from the Ross Building Terrace. Two flights of stairs at the western and eastern ends of the garden once connected it to the York Terrace. Photo courtesy the author.

I now look to my left and I note the Scott Religious Centre, completed in 1974. It was initially conceived of and built as an open depression in the terrace where students could sit and relax. The intent was for them to remain attached to the open air and the sky. When a roof was put on the depression it was connected to the ground floor of the Ross Building where the entrance to the Centre was constructed. There is no entrance to the Centre from the terrace. It is as if the centre is now grounded to the earth beneath it rather than the sky above it, a little odd for a religious centre perhaps.

The amphitheatre space on the Ross terrace intended to be a gathering ground to students but since replaced by the Scott Religious Centre. http://mountmaxwellradio.com/2014/04/03/3714/

The Scott Religious Centre a gray December day in 2014 surrounded by construction material used to patch the leaking floor of the terrace. Photo courtesy the author.

Beyond the Scott Religious Centre stands George Rickey’s mobile sculpture “Four Squares in a Square.” Rickey is part of an internationally recognized group of sculptors who are exhibited on campus. His sculpture provides a conversation between the ordered geometric shapes of the Ross terrace and the random motions of the sculpture. For me, it represents some of the hope that this space could still be.

George Rickey’s “Four Squares in a Square” on a warm summer day. The trees in the Central Square Garden and the Curtis Lecture Halls are seen in the background. Photo courtesy the author.

Another prominent feature of the terrace is a series of evenly spaced concrete planters containing various plants. Like Rickey’s sculpture, they also represent hope, perhaps in the shape of communal garden plots for university members. Yet, it is difficult for campus members to enjoy these features, many access points to the terrace having been restricted, including entrance to the Scott Library.

When leaving the terrace, I return to architectural historian Philip Beesley who helps me put the Ross Building terrace into perspective. He writes that the terrace has a lot in common with other contemporary projects, such as Wallace K. Harrison’s “soaring acropolis” in Albany, New York, and the “lofty piers” of Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh in India. They were architectural feats that aimed to disrupt and change their surroundings. As Beesley writes about the Ross Building:

"…. the sheer primal force of the Ross Building’s structural frame was conceived as a kind of counterpoint, an archaic foundation supporting the turbulent action of a free new society. Amidst the corn and potato fields of southern Ontario, the York University designers conceived a foundation rite embodied in the Ross Complex. The procession led from the east through a march of piers that reached down through the silt plains of agriculture into the bedrock below. Rising up the enormous ramp and through the open frame, the building gave way to the enlightened upper ground of the campus” (Beesley, 2007, 264-5)

Perhaps the several iconic photos of Murray Ross sitting at a desk in the empty fields of the campus illustrate the procession Beesley refers to. By the time the building was finished and the ground covered with concrete, Ross’ desk had travelled from the ground and mud of rural Ontario, up the ramp and terrace to the 9th floor of the Ross Building where he could peer out over his new modern academic domain.

President Murray Ross seated at his desk on the muddy farm field where York University campus is now located. Photo courtesy of York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collection, ASC01639.

From an architectural point of view, the Ross Building is a celebrated complex. In April, 1971, the international College and Universities Conference and Exposition awarded the building a special citation. And in 2009, the City of Toronto assigned the building special heritage status (City of Toronto, 2009, 48).

For several years now, the terrace has been a work site for repairing the leakage of water to the Central Square structure below. The place is most often deserted. The last time I walked there, it was full of innovative graffiti, some of it, perhaps appropriately, urging readers to explore different histories of the university. One of them, for example, reads: “Our struggle is also a struggle of memory.”

In spite of the accolades assigned to the Ross Building by architects, the standard local interpretation of the Ross Building ramp and terrace is that they are failed spaces, as brutal as the architectural style attributed to them, and not faring well in the chilly Canadian winters. In addition, many York students have seen the Ross Building as a fascist expression and part of a police state where the ramp provided access to tanks and military vehicles, the roof was equipped with a helicopter pad, and the 9th floor was the exclusive preserve of the omnipotent president and his entourage of administrators. Student activism, by contrast, was confined to a couple of bear pits in Central Square.

I wonder, though, if the Ross Building ramp and terrace were given a solid chance, and whether, in spite of the absence of the ramp, there is still not some promise in the space. I like the Ross Building terrace, perhaps because I am myself a child of modernism. I grew up in social democratic Sweden in the 1950s and I was raised in an apartment building and played and scraped my knees on a concrete terrace not dissimilar to the Ross Building complex. Dreams and hopes can be nurtured in such places.

Questions

Does architecture tell stories? What stories do the Ross Building ramp and terrace tell?

To what extent was the Ross Building ramp a failure? To what extent is the terrace still a failure?

Is the Ross Building terrace a salvageable space? Can, should and could it become a more central space of the campus environment?

References:

Ancinelli, Nancy (2009).””From Shadows to Sunburn – the Days of the York Ramp” Donated as part of Reflections, Recollections and Reminiscences A project celebrating York’s 50thAnniversary for the Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections by the Retirees of York University. Accession 2009-062.

Beesley, Philip (2007) “Ross Social Sciences and Humanities Building, York University,” pp. 264-73. In Michael McClelland and Graeme Stewart, editors, Concrete Toronto: A Guidebook to Concrete Architecture from the Fifties to the Seventies (Toronto: Coach House Books and E.R.A. Architects)

City of Toronto (2009) Staff Report Action Required: 4700 Keele Street – Inclusion on Heritage Inventory and Intention to Designate under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act. Accessed June 23, 2014 at http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2009/ny/bgrd/backgroundfile-24344.pdf

Wikipedia (2014). Brutalist Architecture. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brutalist_architecture

Woodward, Berton (2005). “The Ramp Killer: YorkU Magazine. October: 28-30. Available at: http://www.yorku.ca/web/about_yorku/yorku_magazine/YorkU_Oct05.pdf