The entrance to Black Creek Pioneer Village

Black Creek Pioneer Village, a re- creation of a white settler farming settlement in southern Ontario from the 1860s, is one of York University’s prominent neighbours. In 2013, the Village reported it attracted 145,000 visitors per year. It even has its own new subway stop (as of December 2017), named Pioneer Village, which is expected to draw even more visitors to the site. The Village often hosts retreats and conferences of Faculties and departments at York University. In 2016, for example, Osgoode Hall Law School held a meeting there on its Strategic Plan 2017-20, and part of it was a discussion on its response to the recent Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, the report that seeks to address the injustices faced by indigenous peoples over the years. Yet the indigenous presence in the Village is largely missing. This is what prompted the following, a story reprinted from the Active History website (slightly edited and complemented with photos), and told by Jesse Thistle, a Metis-Cree scholar, who recounts a personal story about his experience of past and present visits to the village.

The new (2017) subway station named Pioneer Village. It is located on York University grounds and a fair distance from the Village itself.

We are happy to report that the Village has now taken steps, in collaboration with Professors Jennifer Bonnell and Victoria Freeman, Jesse, and the creative directors of Jumblies Theatre, to pursue bringing some Indigenous history into the site’s interpretation.

kiskisiwin – remembering: Challenging Indigenous Erasure in Canada’s Public History Displays

By Jesse Thistle

The short film kiskisiwin – remembering is an intervention in the mythic pioneer fables Canadians tell themselves at public history sites to justify colonial settlement while delegitimizing Indigenous claims to their own ancestral lands on Turtle Island. The logic goes something like this: if nothing or no one existed here before settlement, then it is okay that settler-Canadians exist here now.

This kind of thinking is called terra nullius, Latin for empty land, and it is rampant in many public history sites in Canada. The text below outlines how I, along with Dr. Martha Stiegman and Dr. Anders Sandberg, used film and text to challenge this interpretation at Black Creek Pioneer Village. The materials we produced provide references to learn more about how these sites impacted me as an Indigenous person, as well as the lives of other Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

In 2009, my wife Lucie had an assignment for Dr. Teresa Holmes’s “Anthropology of Tourism” class. Lucie had to visit and evaluate Black Creek Pioneer Village. Though I was basically an uneducated construction worker without much knowledge of critical thought, national narratives, settler hegemony, or whiteness, I tagged along and tried to help where I could. Lucie had a better grasp of these things. As we walked through the village we noticed that the history presented there was problematic on many fronts. It didn’t have 1860s Canada West things like gallows, brothels, police or soldiers’ barracks, or any Indigenous peoples. In her paper, Lucie noted all of these deficiencies and got an A+. Our visit planted within me a seed: why weren’t Indigenous people included in the site? The thought troubled me.

By 2014, I too had found my way into a York University anthropology class, Dr. Sandra Widmer’s “Discourses of Colonialism.” Like Lucie’s class, it had an assignment involving a trip to Black Creek. This time we were asked to critically evaluate the public history on display. As President of York’s Aboriginal Students Association, in doing this assignment, I felt I had an obligation to really watch for the exclusion I noticed when Lucie and I visited five years earlier. With somewhat more education under my belt, I was shocked to see a glaring erasure of Indigenous peoples in virtually all of the village’s dioramas. It was much worse than I’d remembered. In fact, the only place where Indigenous peoples were included at all was in the gift shop in the form of cheap souvenirs visitors could buy. This is no surprise to anyone, I am sure, as most public history sites in Canada relegate Indigenous people to the safety of the gift shop, while the “real” settler history of southern Ontario is reserved onsite for Anglo “whites” only, especially if it represents the 18th and 19th centuries.

The canoe, a gift from Indigenous peoples to European settler society, is now sold in miniature form in the Black Creek Pioneer Village gift shop.

What is more, the Black Creek trip, along with my deeper understanding of their complete erasure of Indigenous peoples, brought back a troubling repressed memory I had from when I had visited the site as a young boy. It was something that really bothered me that I’d learned to forget before this visit. Part of Dr. Widmer’s assignment was to write a letter to Black Creek Pioneer Village to inform them of their lack of Indigenous representation. I figured that I’d let out all my frustration in the letter and do my best to stick up for Indigenous people. Dr. Widmer left it up to us if we wanted the letter mailed or if we would just sit on it. Dr. Widmer gave me an A+. This is the letter I wrote:

April 10, 2014

Dear Education Manager at Black Creek Pioneer Village,

My name is Jesse Thistle. I have visited your site twice in my life: once as a boy of eight on a school trip and another time recently as an adult as part of a field trip for an anthropology class at York University. When I was eight the site was so wondrous; the way your actors plied their trades, made their bread, told their stories, and wore their clothes fired my imagination with such nostalgia that on many occasions I found myself playing pioneers with my brothers in our grandparents’ backyard. I was always the blacksmith, and they the grubby farmers. As the years went on, I promised myself that I would visit Black Creek again but sadly, it never materialized—such is life. Notwithstanding, my boyhood visit did kindle within me a deep love of history that helped me get to university (at thirty-five years of age I might add!) where I am studying to be a historian. Thank you very much for being one of the sparks that lit my historical flame. However, getting to school was not easy for me. I spent the better part of my young adult life homeless and trapped in the revolving door or addiction and incarceration. Apparently, it is inherited and very common in my mother’s people. No matter, at York University I began trying to understand why I was an addict, and why my mother let me and my brothers go into adoption in 1980. To find out, I decided to trace my family history through genealogical charts and proof it against primary and secondary historical resources and voilà, there it was—I was a Cree-Métis from the Road Allowance community of Park Valley (Erin Ferry), Saskatchewan. Me and my brothers were then part of a sociological trend in the ’70s that saw Indigenous children adopted out even though we were raised by our paternal grandparents—that was how I ended up in Toronto. My adoptive paternal grandparents, unfortunately, did not talk to us about our Indigenous heritage—there was such a stigma attached to it back then—I’m sure you are aware of it. As such, I was very uncertain about who I was growing up, or where I belonged, but I always kind of suspected that I was “Indian.”

When I came to Pioneer Village in 1984 that suspicion went away for a moment—I could be just another Euro-pioneer and break the land, farm and fish, just like all my other classmates. However, and sadly, I do remember one kid saying to me with a smug grin on his face: “This isn’t for your kind of people.” All the kids laughed and I remembered being hurt but I didn’t understand what he meant so I just disregarded what he said and tried to enjoy the rest of my visit. His comment, however, remained with me throughout my life. Now that I am older, I realize that his words did have a subconscious impact on me and, in its small way, had contributed to my later addiction issues. Unfortunately, it was just one of the many instances of where I felt marginalized by “Canadians” and “their” exclusionary discourse.

When I came back to Black Creek in March of this year and viewed the site through somewhat trained anthropological and historical eyes, I could see that snotty kid was right. Black Creek is not a narrative written for my “kind,” there are no First Nations/Métis representations in your realist dioramas despite the fact that my people helped Europeans to survive in North America initially. The systems of knowledge associated with land subsistence are vast and take generations to learn in any environment. There is no way European immigrants to North America—the Stongs and others like them—would have known how to live here over the course of one winter without help from Indigenous people—period. Black Creek’s realism takes on even darker tones when one realizes the Anglo-foundation narrative you are presenting is aimed at children and sold as “truth,” leaving many young minds convinced that this area did not have “Indians,” and that no one lived here prior to the Stongs. This historic revisionism remains with them their whole lives and informs how they interact with First Nations people—treating them like just another subset of immigrant “ethnics.” Moreover, the terra nullius (empty land) discourse this is associated with is ignorant, destructive, as well as completely false as Ontario has been continuously occupied by First Nations people since the last ice age, 12 000 years ago! I could go on at length as to which First Nations people lived around the Toronto area at what time but for the purposes of this letter I will only impart that the last First Nations people who lived here were the Mississaugas of the New Credit. The Mississaugas lost the land now encompassing the GTA to Upper Canadian bureaucrats who underhandedly signed unfair and unjust, and now proven, illegal treaties with Mississaugas’ Chiefs on the 1778-79 Toronto “purchases” and 1805 Toronto “Confirmation” and that is how the land was freed up and “given” to the Stongs. Upper Canada land was certainly not free, empty, nor wild—these are Euro-misconceptions. Thousands of years of wildlife management and land stewardship in Ontario had created a hearty symbiotic hunting and fishing ground that served the needs of First Nations people; it merely appeared “wild,” much like a well-manicured and rangered Algonquin Park does to us now. Furthermore, the concept of “Wild Empty Land” has Biblical connotations (Satan was thought to live in the “wilderness,” hence the Papal Bulls of the 1500s and 1600s were designed to save savages from his trickery) and is tied to medieval Europe’s moral fetishization of cities. Lastly, the absurdity of terra nullius set to your Anglo realist foundation myth of Upper Canada denies the fact that Euro-agrarian settlement has only existed in Ontario for six maybe seven generations, while semi-sedentary First Nations settlement existed here for over five hundred to two thousand generations! To paint a better picture of Ontario’s long First Nations history imagine that the whole of human settlement here in North America neatly fit into one year—we’ll use the most conservative estimation of 12 000 years of First Nations habitation: Columbus would arrive in the “New World” at noon December 25, at 10:30 p.m.; on December 27 Samuel de Champlain would found Quebec; and the Dominion of Canada would be created at 2:00 a.m. on December 30 (The idea of putting the whole human history of North America into the chronology of one year belongs to scholar Sarah Carter, I just recalculated it for a more dramatic effect). When put in context, the realist discourse you employ—which narrowly focuses on the last few minutes of the last day of the historiographical year—to obliterate First Nations from their rightful place as co-founders of Upper Canada is, to use a colloquial term, a big fish story.

Do not lose heart. Please continue reading, there is a point to all my historical revisionism—although it isn’t called revisionism when you’re simply telling the truth. When Black Creek Pioneer Village was created in the early 1960s it reflected the majority values of Anglo-descended Canadians of that time. So, in a way, it isn’t your fault that the historiography you perpetuate is so incredibly myopic, racist, and anachronistic. We, your “noble” Indigenous super friends, forgive you—but we do expect you to change things. As well, I think you should be aware that Indigenous populations are the fastest growing demographic in Canada by leaps and bounds, even with massive immigration, so it is in your best financial interest to write us into your myth cause we’ll be the ones lining up and paying your gate fees in fifty years to see ourselves reflected in your realist colonial “mirror.” And I promise, if you start to include us now, when our Indigenous numbers overcome settler numbers—a real possibility if things keep going the way they are, we won’t write you out of our foundation myth, you have my word on it.

Warmly,

Jesse Adrian Thistle

President of the Aboriginal Students Association at York University

The decision to mail the letter, it seems, got lost in the turmoil of my undergrad. It’s not like I didn’t want to mail it, I just got buried in pow wow and feast planning, being President of the Aboriginal Students Association at York University and all that entails, and trying to stay afloat amid the torrent of crappy undergrad papers I had to write.

Near the end of the 2014-15 school year, however, I was approached by Dr. Jin Haritaworn and asked to speak on a panel for the Environmental Studies Seminar Series: “Transforming Violent Environments: Antiracist and Anti-Colonial Classrooms and Campuses.” Jin informed me that the panel was to focus on York’s campus and I thought instantly of sharing the letter I’d written in Dr. Winder’s class. I thought I should read it because Black Creek is situated right next to York University. After all, being the President of the Aboriginal Students Association at York University, it was my duty to go and speak up for the racism many York Indigenous students felt every day at school, and that some described to me after going to the village themselves.

On January 20, 2015, I read my letter aloud and the crowd loved it; many people cheered; a few jumped out of their seats; some had questions; and one man approached me afterwards and asked me if I wanted to make something more of it. His name was Dr. Anders Sandberg, a full professor in York’s Environmental Studies faculty. Anders told me that he believed the letter would make a good short film and book chapter and that he could use it for his Alternative Campus Tour. The Tour showcases local history on and around the York campus. Anders then invited me to be a tour guide on one of his Jane’s Walks in May 2015 and I took him up on the offer.

A few months passed and it looked like the letter would go back into my desk drawer and collect dust. That is, until Anders called me up one summer day in July and said that he’d found someone to direct the film and that we’d better meet in his office to plan it out. The filmmaker was Dr. Martha Steigman, a recent hire in York University’s Faculty of Environmental Studies. Martha was an established filmmaker with connections in Montreal who had made films with many Indigenous communities in northern Quebec and in the Maritimes.

In that July meeting the three of us schemed. We planned out a script writing session, charted out how we could make a book chapter based loosely on the information in the letter, and how we could confront the problematic history presented in places like Black Creek. At the end of it, Martha and I were to do the script and film, while Anders was to focus on the book chapter for his upcoming edited collection, Methodological Challenges in Nature-Culture and Environmental History Research.

The book materialized, relatively quickly, after Anders and I did a reconnaissance mission of the site collecting data for our piece. In consultation with Martha and I, Anders toiled away on the book chapter for seven months. “But where am I?: Reflections on digital activism promoting Indigenous peoples’ presence in a Canadian heritage village” was published earlier in 2017.[1]

The filming for the project took much longer than anticipated, one year, for which Anders and Martha got internal funds from the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York. The overextended filming happened partly because we had to secure permits to film at Black Creek in a timely fashion before the fall season ended (the village closes in winter). Martha’s director’s eye brought to life my words and made them into beautiful images. The film launched nationally on June 27, 2017 on the National Screen Institute website and it is currently going “viral” online, a testament that others in Canada feel we must fix our broken and exclusionary public history and education institutions and start recognizing that Indigenous peoples were here first and thus have an inherent right to the land.

For what it’s worth, with York University history professor Jennifer Bonnell, I met with Black Creek’s managing directors in October 2016. I showed them the film and things look hopeful currently. The people at Black Creek were moved by the personal angle of kiskisiwin, and Dr. Bonnell, to the best of my knowledge, has been working with Black Creek to change their narrative and integrate Indigenous peoples into their onsite history displays, not just in the gift shop.

I lay out this brief sketch of how the film and book chapter were created in order to show what a positive intervention into public history looks like from the ground up, and how sometimes a small idea—even if it’s just an angry letter from a naive Indigenous undergrad trying to do the right thing—can go on to influence how public history is done. It also demonstrates how collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars, when we work together earnestly and openly, can actually affect change when new interventions are given a platform to succeed. In essence, kiskisiwin and the chapter “But where am I,” was our little way of calling Black Creek’s attention towards a few of the Calls to Actions outlined in the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada report, specifically number 63 and the whole section “Museums and Archives.”

Jesse Thistle is an assistant professor in the Department of Equity Studies where he teaches the history of Métis people living on road allowances – makeshift communities built on Crown land along roads and railways on the Canadian Prairies in the 20th century. Jesse is Metis Cree and a Doctoral Candidate in the Department of History at York University. He is a Trudeau and Vanier Scholar.

[1] L. Anders Sandberg, Martha Stiegman, and Jesse Thistle, “But where am I?” Reflections on digital activism promoting Indigenous peoples’ presence in a Canadian heritage village,” Methodological Challenges in Nature-Culture and Environmental History Research. Eds. Jocelyn Thorpe, Stephanie Rutherford, and L. Anders Sandberg (New York: Routledge, 2017).

Black Creek Pioneer Village: A Brief Photographic Essay

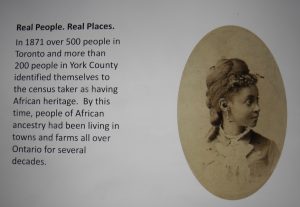

Real People. Real Places. In order to be real people in real places, people in the 1860s had to be part of the Canada Census. A small exhibit from the Archives of Ontario at Black Creek Pioneer Village pays tribute to another marginalized group, the Black community, but only those Black folks who were part of the official record. Migrant workers, and settlers and traders who move about, like many members of the Indigenous community, were not and are not part of the “real people.”

The school room in Black Creek Pioneer Village. Here children were socialized into Canadian settler culture, a culture that saw Indigenous peoples as backward and inevitably destined to assimilate into and become part of settler society.

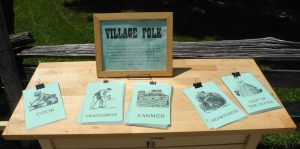

The village folks clearly do not include Indigenous people.

A canoe constructed according to Indigenous peoples’ principles is hanging in the water-powered grist mill in Black Creek Pioneer Village but there is no attribution to who made it or where it comes from.

The courtroom in the Village. Notice the Union Jack and the photos of Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. The courts were powerful institutions articulating and enforcing European property rights in land, an alien system to local Indigenous peoples.

The Dalziel Pioneer Plot 1828. Grave plots ensure the permanence of settler culture in the landscape. Though there are some ossuaries housing Indigenous remains in the vicinity, most Indigenous grave sites remain unknown and/or have been buried under streets, subdivisions and other forms of development.

The Dalziel Barn. Meticulously researched and with its own website (http://dalzielbarn.com/home.html), the Dalziel barn at Black Creek Pioneer Village stands as a testament to the documentation, care and publicity accorded the European settler society and economy. No such efforts have been spent on documenting the Indigenous presence in the area.