In 2008, Mark Osbaldeston wrote a book called Unbuilt Toronto: A History of a City That Could Have Been documenting and telling the stories surrounding unrealized building proposals in the city. This short reflection is inspired by that idea. But it is also much more. It also reflects on the questions and trepidations involved with a public institution becoming less reliant on public financing and more entangled in raising money from the private sector

I was relieved to sit in on the last Committee of Instruction meeting of my Faculty (Environmental Studies) before the summer break in 2017. Finally, I thought, some time for myself. Usually, CofIs, as we call them, are pretty uneventful, especially the last one of the academic year, but at this one the Dean announced that the Faculty had struck a funding coup, securing money from Walker Environmental, a private company, to build a Walker Pavilion in conjunction with Maloca Garden, a community garden that sits precariously on the university grounds and that is operated by student volunteers. The Dean introduced the company as a sustainable business concerned with recycling and environmental matters, and also being earnest and sincere in their business practices. Most members of Council, including me, heard about this arrangement for the very first time.

In conjunction with the announcement, the Dean provided a powerpoint presentation and showcased a little booklet entitled “Building the Walker Pavilion at Maloca Community Garden: A Proposal Prepared for Walker Industries.” It contained a little history of the faculty and sketches of the prospective pavilion.

The Pavilion that was not to be! Notice the sterility of the greenery surrounding the building, the raised path leading to it, and the solar panels that were intended to power the building. The expression “sustainable – off the grid” accompanied the promotional image.

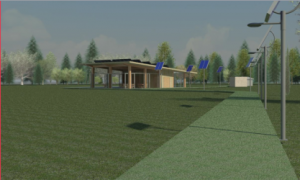

The Pavilion up close. Note the bike stands, the open design, and the solar panels on the roof. The expression “sustainable – solar” was coined with this image.

Many members of Council were impressed with the sketches and salivated over the prospects of such a splendid building on the campus. Many of them imagined and commented on how the pavilion may look beside the Maloca Garden and what functions it may fulfill in their courses and how students may benefit from the place.

However, by the end of the summer, the Interim Dean announced that Walker Environmental had withdrawn its offer to fund the pavilion, a decision taken after a group of company officials had visited the site and determined that the university had not exhibited sufficient support for the Maloca Garden to warrant financial assistance from the company. Go figure, a private profit-seeking company, typically the bane of our attacks (perhaps in this case even a green washer), lectured us, the public York University, the Faculty of Environmental Studies (Hmphh!) for our lack of efforts in supporting a local community campus garden.

Maloca Garden. Note the anarchy of plots and plants, in contrast to the neat lines of regularity of the planned Pavilion. Maybe the marriage of the Pavilion and Maloca Garden was never meant to be!

To me, the brief encounter between FES and Walker Environmental opened up several questions and cautions on the process, terms, and extent to which a university and its faculties and departments should (or should not) become involved, dependent on, and beholden to private companies for financial support.

I contemplated these questions as I went down to Maloca Garden and stood among its little garden plots, imagining what the Walker Pavilion might have looked like beside it. The first question that the Walker experience brought to my mind had to do with the type of business a university may chose or accept to engage with and the research that should be expended in finding out about its activities and connections. When first introducing Walker Environmental, the Dean presented the company as a good corporate citizen engaged with environmental issues.

A little more research would have revealed that Walker Environmental is a division of Walker Industries, a company that also has a mining division, extracting aggregates, that is, sand, stone and gravel, from twelve pits and quarries. Aggregates is in fact the core of Walker Industries’ business and the company makes no apologies for this pursuit, using similar arguments as their competitors in speaking for the industry, contending that there is a growing demand for aggregates that needs to be met, aggregate use is a mere interim use, rehabilitation of used lands is therefore possible, and extraction can co-exist in harmony with local residents and environments.

Critics, such as myself, point out, however, that aggregate extraction is not environmentally benign, and arguably not a business that a Faculty of Environmental Studies should associate with. Torontonians may recall the recent super quarry proposal at Melanchton that failed to take off in light of huge protests in the region and throughout the Greater Toronto Area. The opponents of the proposal focused on the dire consequences for water protection and food production in the region should the quarry have proceeded.

The industry and industry association, however, spoke up in united support of this venture and lamented the withdrawal of the proposal. Here is an extract from the Toronto Star that tells a little about how Walker Aggregates Division figured in the story:

Ken Lucyshyn, vice-president of Walker Aggregates, a family-run company based in the Niagara region, said the decision of Highland, a billion-dollar hedge fund, to pull out of the process makes him concerned about his ability to secure new sites in the future.

“We spend millions of dollars on an application and there’s no guarantee you’re going to get it. When we start to worry about the risk reward … a small producer, how does he afford that?' he said.

Walker Aggregates, which operates 12 sites across southern Ontario, has outstanding applications to expand three of those sites. Despite getting the go-ahead from the Ontario Municipal Board, one of those applications is being challenged by the Niagara Escarpment Commission.

Toronto Star, 22 November 2012

In a subsequent Ontario Municipal Board 2015 decision, Walker got the go-ahead to expand its quarry on the Niagara Escarpment referred to in the above quotation. The majority decision not only endorsed the controversial principle of no net loss, that the environmental costs of a development in one place can be compensated by a conservation measure at a different site, but also that the Niagara Escarpment conservation legislation counts for naught in light of the province of Ontario’s designation of aggregates as an “essential public good.”

How do I know about all these things? Well, I have spent part of my career interrogating and questioning the aggregate industry’s positions and self-promoting discourses. I have published academic journal articles on the Dufferin Aggregates’ Milton Quarry expansion and James Dick’s proposal to establish a pit in Caledon. I have also made my views known at various hearings on aggregate mine expansions, urging policy makers and politicians to halt or slow the pace and extent of the industry’s expansion as well as to look for alternatives. I have also tried to make connections between climate change and the aggregate sector by pointing out that the whole aggregate cycle is highly carbon-intensive and much of the aggregate is used as a foundation for the carbon economy. Over half of all aggregates extracted, for example, go to road building. We, therefore, need to be cognizant of the impact of this industry, just like the oil and gas industry. I don’t really know who coined the expression leave the oil in the soil, but I think it is a motto many of us wouldn’t question. Nor would we likely accept a sponsorship or endowment from an oil and gas company, likely not even its environmental divisions.

I and one of my students, Lisa Wallace have coined another expression inspired by the leave the oil in the soil one, that is, “leave the sand in the land, let the stone alone” to call attention to the connections between the carboniferous and calciferous sectors. This is a difficult task. As a society generally, we are a lot less attentive and critical of the aggregate sector, despite its huge presence, expansion and social and environmental impacts globally. Yes, there are protests against the industry, but typically on a site-by-site basis. A few of these struggles have been successful, such as at Melanchton, usually at places where the protesters are wealthy professionals who are well connected politically, leaving other areas open to aggregate extraction.

Yet, in spite of these credentials, I was only made aware of the Walker Brothers’ prospective gift after the deal had already been made (though later reneged).

A second question that bothered me by the Walker funding effort related to the confidentiality that surrounded the solicitation of their private funds. The typical rationale for secrecy with regards to discussions with funders is to protect the identity of a potential donor. But what does confidential mean and when may the concept compromise a negotiation? Is there a danger, if the group is too small, that negotiations between funders and potential recipients become too personal and too cozy? Advancement personnel’s visions may be clouded by the urgency to raise money which is, after all, what they are mandated to do. In the face of drastic cutbacks, Deans are more and more occupied with budget lines, and more and more of their time is preoccupied with fund raising. When our previous Dean finished her term, one of her achievements, recorded in the minutes of Faculty Council, was her ability to raise $6.4 million in pledges over the past 5 years. In this situation, it is perhaps not desirable to discuss let alone reveal the status of a donor company in front of group of cranky professors. Or may it have helped the situation? Should Walker Environmental have been made aware of some Faculty members’ critical stand on the company? Should a more open discussion about Walker Environmental as a benefactor been conducted in the Faculty? Might a more frank interaction and a more open discussion within the Faculty have led to a much earlier parting of paths? Might this have saved both parties time and money? How much time and money did the Faculty invest in its negotiations with Walker Environmental? Who paid for the promotional material and architectural drawings of the building? And who came up with the bright idea to propose a wooden structure to a company whose main product line is aggregates?

The Marriage of the Pavilion and Maloca. Note the images of Maloca Garden lining the side of the image. Note also the wood used in the Pavilion’s construction, defying the use of aggregates and concrete material produced and promoted by Walker Brothers. Might Walker Brothers have objected to this approach? Would they have preferred the use of recycled concrete? The expression “sustainable – reclaimed timber” went together with this image.

As I perused the promotional material in more detail, I also wondered if Walker Industries, or any other private business, would have been totally sold on its pitch. The first sentence of the executive summary read: “Food insecurity and hunger are present everywhere, from urban slums to cities in industrialized countries like Canada. While a growing food movement advocates sustainable agriculture by eating food produced on local family farms, many low-income communities have insufficient access to healthy food, becoming so-called “food deserts” where fast food is more common than fresh food.” The document went on to write about food as a human right, food justice, food sovereignty, indigenous knowledge rights, and it featured short biographies of faculty members, students and alumni who work in these fields. It then invited “Walker Industries to take a leadership role in helping to augment food security efforts in neighbouring low-income communities in Toronto and York Region.” I loved the document. It told an honest story about the Faculty and it surely showed, contrary to Walker’s claims, that FES (though perhaps not York) is committed to Maloca. But what did Walker think about the document in the end? Could it be that the company walked away from the initiative given the rights and social justice language employed in the document?

A third question that bothered me about the Walker experience related to the compromises a university may have to enter into through the branding, publicity and naming attached to private funding initiatives. At the meeting where the Walker decision was made public, faculty members asked the Dean the question what is Walker’s presence going to be on campus besides giving its name to a building. Her response was that Walker employees would have had access to the facility and surroundings on an annual basis. But would they also have been able to show off their standard rationales for the aggregate industry’s prominent presence, including the most recent efforts to develop a sustainable certification for green aggregates (not dissimilar from ethical oil)? At the time, it struck me as a little ironic that the company could cozy up to a Faculty of Environmental Studies and a local food initiative given the centrality of food issues in defeating the Melanchton project. It looked like Walker had struck a PR coup here for sure.

The Walker Environmental initiative called my attention to the way money rules when it comes to name recognition at York University. Some time ago I approached my former Dean about naming a campus feature after a retired FES faculty member who had been prominent in its creation, not through money, but through sheer sweat, labour and determination. I was told, sure, it may be possible, but the university requires that you first cough up some money, and no small amount either. More recently, the President scuttled another widely supported naming effort in the Faculty because it was not accompanied with millions of dollars. In contrast, the Schulichs, Varis, Dahdalehs, Lassondes, Bergerons, and Walkers of the world, often (but not always) without no or little connection to York, but with lots of money (and never mind how they got it, and never mind what they say about York in public) can buy a piece of us without a problem. It is a tough and tricky ground to navigate. I decided to walk by some of these buildings when I strolled back from Maloca to the Faculty.

But could I be wrong about all this? What are some of the good things we could have gained from the Walker Environmental initiative? Perhaps the “Environmental” rather than the “Aggregates” Division would have been the most prominently displayed at the building. And yes, I know, there are good and well-meaning people in industry, and Walker Environmental has since contributed a day of community work to Maloca Garden. And yes, I know, that the Faculty is under enormous pressure to raise private money and that it takes a lot of effort, pluck, strategy, and effort to get that money. Perhaps the Walker Environmental initiative would also have been a great way to raise money for the faculty in a smart way. In spite of many of its faculty members being critical of the extractive industry sector, if successful, we could have congratulated ourselves on landing a major endowment from Walker (a target of our criticisms). The joke would have been on Walker and not on us. The planned building looked great and there were also provisions to renovate the nearby Hoover House, a mid-19th century heritage-designated farm house that is now abandoned and in a sorry and dilapidated condition. It may have been a great thing to have had more support for Maloca Garden and also, as one other faculty member proposed, some room for community and performance arts in the building. And, hey, the Walker name on the building would have been a small prize to pay. After all, some of us wear apparel with the Nike swoosh on it, and we likely paid for it to boot. And, finally, the effort to secure funding from Walker Environmental may have been worth the effort even if it didn’t succeed. This is how the game is played. If you don’t try, you will never win. And when you try, you win some, and you lose some. Perhaps this is the way we have to think and act in the context of the neoliberal/enterprise university.

I think some suggestions flow from the above:

- We need to be more vigilant in researching potential donors and to engage more faculty members, staff and students in that endeavour.

- If we are to seek out wealthy donors, we need to seek out those who are self-reflexive and self-critical about their business activities and accumulated wealth, and who may thereby be open to fund social equity and justice projects that may be critical of the financial and legislative infrastructure that allowed their private capital accumulation in the first place.

- We need to abandon a slavish adherence to selling naming privileges for money–up-front. We need to question the absolute authority of the Administration and Advancement people in telling us to toe this line. The SHARP budget model will soon ask all Departments and Faculties to manage their own costs and revenues. The same should be true for other activities, such as naming ventures. It may well be, for example, that naming a Faculty or building after a prominent person (but who may not have any money), may yield rewards in other ways, perhaps through increased exposure, increased enrolment, and the attraction of the right students to our programs.

References:

Faculty of Environmental Studies, York University. 2017. Building the Walker Pavilion at Maloca Community Garden: A Proposal Prepared for Walker Industries. On file at the Dean’s Office, Faculty of Environmental Studies, York University.