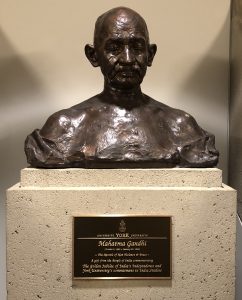

A sunny day in late December 2018 turned out to be my one-day immersion course on India. It was almost Christmas and I went to one of the stores at York Lanes and bought some sweatshirts with York logos on them. I discovered that they were made in India and, so the enthusiastic sales clerk assured me, of the very best cotton quality. I also had a curried veggie wrap for lunch at Indian Flavour, an Indian Restaurant in York Lanes. But more importantly, I went to the Scott Library to return a couple of books and then, as is my habit, I looked around a little and I was drawn to the statue of Gandhi (1869-1948) that is located close to a stairway in the back portions of the Library’s main floor. It shows a bust of Gandhi in bronze with an accompanying plaque with the inscription “The Apostle of Non-Violence and Peace” and noting that the statue was a gift from the people of India commemorating the Golden Jubilee of India’s Independence [1997] and York University’s commitment to India Studies.

Such statues celebrating Gandhi can be found in 70 countries across the globe. In India itself, they are equally if not even more prolific in numbers and there are sculptors who specialize in making them. But the adulations for Gandhi do not stop there. The blockbuster film on Gandhi by Richard Attenborough featuring Ben Kingsley in the lead role is an example of a hagiographic portrayal of Gandhi produced in the West. In 1983, the film won several Oscars, among them best film for Attenborough and best leading actor for Kingsley. As I am writing in March 2019, the film is showing on Netflix.

And in Toronto, the Vishnu Mandir, the first architecturally structured Hindu temple in Canada in Richmond Hill established in 1982, opened its “Canadian Museum of Hindu Civilization” in 2004, allegedly the first of its kind in North America, which features Gandhi prominently at the temple, including a Can$300,000 statue in its Peace Park.

In the Museum, there is a Wall of Peace that is aimed “to send a message of harmony among all religions and to stimulate peace consciousness in all nations.” It contains individuals and symbols of major religions, Lord Mahavir of Jainism, Lord Buddha, Lord Jesus Christ, Star of David, The Symbol of Islam, Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, and the AUM of Hinduism.

It was not the first time I visited and gazed at the Gandhi statue in the library. I had in fact done some research on the history of the statue and had learnt from the York Gazette, the official news organ of the university at the time, that it was presented to the university during a “brief ceremony” in January 1998. York was reported to be a recipient of the bust “in recognition of the University’s several connections with India, including the Centre for Asian Studies, the scholarly activities of a number of faculty members and the large number of students with an Indian heritage.” A photo accompanied the article with the then York University President Lorna Marsden present with India’s general consul and Dr. Rasik Morzaria, a member of the York Board of Governors. No faculty members or students appear to have been at the presentation. The article indicated, though, that “[a]t a later formal ceremony, the Gandhi sculpture will be permanently installed near the reflecting pool in the Scott Library” (Gazette, 1998).

Is Gandhi worthy of such adulation? What aspects of the man are revealed and concealed by the statue? What broader questions does the statue invite us to ask? What role should society generally and universities specifically play in sponsoring and accommodating statues of famous and prominent people and politicians in public places and on campuses? What criteria should be used in making the decisions to welcome such statues? Who should set such criteria and who should make the selections?

In some respects Gandhi is a significant political figure. There is a substantial scholarly community who supports the position that he played a key role in the Indian independence movement. Internationally, Albert Einstein, Nelson Mandela and Dr. Martin Luther King embraced his views, and on 2 October 2007, on the 150th birthday of Gandhi, the UN General Assembly established the International Day of Non-Violence. However, the positive images of Gandhi that are so well known and fostered internationally hide the fact that he is also a hugely controversial person in India, both among scholars and Indians at large. Among Hindus, for example, some feel that Gandhi, in the lead up to independence, provided too many concessions to the Muslims, a position that caused his murder. The assasin, Nathuram Godse, is now celebrated by his own statue, erected by members of the Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha, a radical right-wing Hindu nationalist party (India Times, 2016).

There are other groups who are critical of Gandhi's legacy. In Africa, at the University of Ghana, faculty members successfully challenged the presence of a Gandhi statue on the campus and had it removed in 2018. The gist of their criticism was that Gandhi, when living in South Africa, viewed Blacks as inferior to Whites and Indians. The statue has since been re-instated in the capital city of Ghana, Accra, allegedly under the pressure to maintain cordial relationship with India, which is an important trading partner. The protests over a Gandhi statue in Malawi speaks to a similar situation, where one observer suggests that Malawi, a poor country, was blackmailed into receiving a Gandhi statue as part of a building deal with India worth $10 million. In Senegal, the controversial Renaissance Monument in Dakar, hosts a section on Gandhi, and the state of India has long-standing trading and cultural exchange relations with Senegal that include a heavy content on Gandhi (India-Senegal Relations, 2018). In Canada, at Carleton University in Ottawa, there is an initiative, though so far unsuccessful, by the Institute of African Studies Student Association to have their statue of Gandhi removed, an effort that is supported by the faculty members at the University of Ghana (Oke 2018).

Left intellectual and historian Ramachandra Guha has pointed out that Gandhi's views on race evolved with age. While a racist in his 20s, believing in a hierarchy of races, with Europeans at the top, Indians second, and Blacks at the bottom, he changed his views in his 30s. At that time, he believed that Africans should be absolutely put on an equal footing with Indians and Europeans. Yet there are those who feel that Gandhi’s early views on race should not be excused but open to question and debate, a point reinforced by his name becoming an element bound up with the geopolitics of foreign policy, trade and investment on the African sub-continent (and perhaps beyond)(Power, 2019).

The Dalits, the untouchables, the lowest caste in India, are also critical of Gandhi, though he was by no means unsympathetic to their plight. Gandhi himself came from the Vaisya/Bania caste, pretty lower-middle class and definitely not wealthy. He was a strong advocate of equality and fought for the abolishment of untouchability (including leading several anti-untouchability campaigns), repeatedly saying it was a disgrace and a stain on Hinduism and India.

Yet critics point to Gandhi’s opposition to the Dalits' equality in the Indian Constitution. Gandhi felt strongly that the caste system was central to Hindu society and challenging it constituted a threat to Hindu society. He believed caste had to be reformed rather than abolished (because he thought there was some merit to a social division of labour).

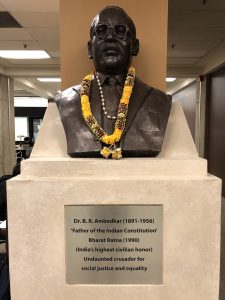

The most prominent of Gandhi’s opponents, Dr. B.F. Ambedkar, a Dalit himself, lobbied very hard for the organization of the Dalit and their inclusion as equals in Indian society. Ambedkar believed (against Gandhi) that it was not just untouchability that was the problem but the very institution of caste. In fact, at the other end of the library, in one of the student reading rooms, stands a statue of Dr. Ambedkar. Erected in 2016, the size of the statue is equal to that of Gandhi, and the plinths on which the busts stand look very similar.

There are three plaques on the Ambedkar statue. The front one reads “Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (1891-1956) “Father of the Indian Constitution”; Bharat Ratna (1990) (India’s highest civilian honor); Undaunted crusader for social justice and equality.” The other two plaques are situated on the side of the plinth and contain quotes from Dr. Ambedkar. They read: “I measure the progress of a community by the degree of progress women have achieved” and “Education is something which ought to be brought within reach of everyone.”

The Dr. Ambedkar International Mission (AIM), Toronto, donated the bust to the Faculty of Liberal Arts & Professional Studies. This was no doubt part of a wider effort of the AIM, as the University of British Columbia and Simon Fraser University were recipients as well. These institutions also benefit from an annual lecture in honour of Dr. Ambedkar.

The statue of Dr. Ambedkar, always generously adorned, a clear contrast to the Gandhi statue

The presence of the Gandhi statue in the Scott Library (and especially the existence of the Ambedkar statue a short distance away), could invite, as it has elsewhere, a discussion about Gandhi’s stance on race and caste. The community of Davis, California, stands out as fairly typical where such a discussion has happened. Here community members were pitted against each other over the erection of a Gandhi statue. The proponents won the battle on the basis of the standard arguments that portray Gandhi as a non-violent peacemaker and father of the independent nation state of India. One resident, for example, stated that “We want nothing more than to see Gandhi’s life and lessons — in particular his commitment to love, inclusion and non-violence — to continue to teach and inspire new generations of Davis citizens and those who visit our city.” The opponents, on the other hand, claimed that Gandhi came from a wealthy family of a higher caste and worked to alienate the Dalit. One sign carried by the protestors read “Gandhi: Creator of India’s Poor, Ambedkar: Father of India’s Poor.”

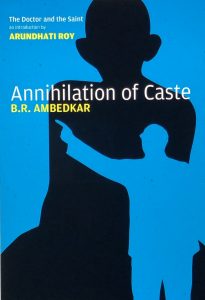

The contrasting positions on caste by Gandhi and Ambedkar illustrated on a book cover.

There is yet another well documented but not so well known critique of Gandhi. It is that he acted inappropriately against young women, even his grand niece, sleeping naked with them and conducting experiments with them to test his long-standing commitment to celibacy. Apparently, Gandhi ceased being intimate with his wife at an early stage in order to cleanse himself and achieve a status of purity. When his wife died in 1944, Gandhi took to the practice of sleeping naked with young women. This practice was part of his general philosophy of austerity, non-violence and the search for a state of freedom from bodily desires. Gandhi spoke openly about this, seeing it as a religious/spiritual practice, in spite of several of his friends criticizing him for it. In other words, this is not something he did illicitly or tried to hide. Whether misguided or not, he genuinely thought he was being ethical/spiritual. One group of scholars’ view is that Gandhi, then in his 70s, never sexually abused any of these young women.

Others, however, have written more critically of Gandhi’s sexual celibacy, exploring in particular the impact on the young women he slept with. Rita Banerji points out that many of Gandhi’s contemporaries, friends, colleagues and employees, were appalled by his behaviour and urged him to stop, though he seldom listened, and, when doing so, he did it with reluctance. They also suggest that some of the young women suffered from mental depression as a function of their nightly encounters with Gandhi. How do we view his “experiments” to sleep naked with young women later in life to test his commitment to sexual abstinence? Do we excuse the practice as legitimate or as the misguided steps of an old man in the later parts of his life?

Though well documented, why is there such a silence on Gandhi’s actions on sexual abstinence, nakedness, and his relationship with young women? One Indian observer provides one speculative answer in the following:

"The puzzle remains – why the hypocrisy of the present generation of leaders about Gandhi? Gandhi alive was an embarrassment but Gandhi dead became an asset! It became even more convenient to use him by putting him on a pedestal and hiding his warts and wrinkles. A myth was quickly developed making him a martyr and saint. People outside India readily embraced this oriental myth. After all, is not myth-making an integral part of nation building?" (Vijayendra, nd)

The sincerity of Gandhi’s sexual abstinence has also been questioned by his intimate relationship with Hermann Kallenbach, a Jewish architect of Lithuanian origin who built a deep friendship with Gandhi during his time in South Africa. In his correspondence with Kallenbach, Gandhi spoke intimately about his affection for Kallenbach, how he misses him, how “Mrs. Gandhi” (his wife) is making his life miserable, and signing his letter “with love.” There is no direct evidence, though some people have charged so, that Gandhi was homosexual. But the correspondence certainly reveals a form of homoeroticism or intimacy that betray Gandhi’s vows of abstinence and disavowal of sexual feelings. He was a person with sexual drives and feelings like most other people.

I contemplate the various positions on the traits of Gandhi when standing and looking at the statue in the Library. Perhaps I am a little too intensively in deep thought, because a couple of Library workers ask me if they could be of assistance. Of course, perhaps they could have, and I regret I didn’t ask, but at the time I said no thank you because I was too caught up in my own thoughts.

What about the presence of the Gandhi statue on campus? Should it be challenged? And, if so, what should that challenge look like? Should the statue be removed, following the example of the University of Ghana? Do we excuse great men like Gandhi of questionable actions, however well-intended, in light of their other achievements and contributions to society? Do such actions pale in comparisons to their other deeds? Should, in such instances, the abuses be ignored or de-emphasized in the telling and celebrating of their legacies? Or, should the dominant narrative of Gandhi’s legacy stand, letting him remain the apostle of non-violence and peace that most of the world know him as? Or should there at least be a way of providing a public record that lays out the various positions on Gandhi and his legacy?

More generally, there are specific questions to be asked too. How do statues figure in the physical environments and the geopolitics of nations and institutions, like a university? Who approved the welcoming of the Gandhi and Ambedkar statues on campus? What criteria did they employ to approve them? Is there a connection between the welcoming of the two statues? What does it mean that the state of India has two statues represented at the University while some states or nations (such as Indigenous ones), with arguably similarly significant leaders, are not represented at all? To what extent can nation states, like India, or private foundations, “buy” a place for statues of political figures that they represent? How prone are University Administrations to accept or reject statues in order not to offend the governments that support them, the businesses that sponsor them, and the foreign students who pay the tuition fees that universities rely on at an increasing rate?

These are questions that are especially relevant at a university (a place of learning and questioning) where the presence of commemorative statues should never be taken for granted, and where there should always be a conversation/debate about them, the decision-making to institute them, the ethico-politics of the figures they commemorate, and the broader social values and institutions they represent.

_________________________________________

The unveilings of the statues of Gandhi and Ambedkar were similar in many ways. Both events were announced publicly, and York officials and Indian dignitaries spoke about the merits of both men, but there were also differences between the two events.

The ceremony organized for the installation of the Gandhi bust occurred on 1 October 1998, the 50th birthday of the formation of the state of India. The original offer of the bust came from Consul General Rajiv Bhatia to George Fallis, Dean of the Faculty of Arts. But the event was presided over by President Lorna Marsden and the plaque on the statue carried the University Coat of Arms. And though the University issued a media release for the event, there was no official media reporting afterward, and there is no documentation of the event on the world wide web [Office of the President’s files, University Archives, fonds F0073, file 2006-018/002(04)].

The unveiling of the Ambedkar statue occurred much later, on 2 December 2015, the 125 birthday of Ambedkar. And, in contrast to the Gandhi unveiling, the President was not in attendance, the University Coat of Arms was absent from the plaques (instead the Faculty of Liberal Arts & Professional Studies appeared as sponsor), but the publicity surrounding the event was extensive. The Dean of the Faculty Professor Ananya Mukherjee-Reed spoke about how Ambedkar’s focus on social and economic justice corresponds with the core values of York University. A commemorative booklet, still available on the world wide web, was released with the event with several Indian dignitaries and scholars commenting on the life and career of Dr. Ambedkar.

On only one occasion in the news release and in the commemorative booklet is Gandhi mentioned, when the Dean of the Osgoode Law School Professor Lorne Sossin stated that in a recent opinion poll in India, yielding two million votes, Dr. Ambedkar was voted the “Greatest Indian since Gandhi.”

What can we read into these differences? Did the presidential reception and the use of the York logo on the Gandhi statue constitute a form of special treatment? Did the lesser reception of the Ambedkar statue have something to do with the University not wanting to offend the state of India, Gandhi representing the true India while Ambedkar standing for a lesser one? Was and is the Ambedkar statue and its public commemoration on the world wide web an initiative to counter, balance, or initiate a discussion on the merits of these two Indian personalities. Has this happened? If not, their presence constitutes a great opportunity to do so.

References:

Banerji, R. (nd) “Gandhi Used His Position to Sexually Exploit Young Women. The Way WE React to This Matters Even Today,” YKA Youth Ki Awaaz. https://www.youthkiawaaz.com/2013/10/gandhi-used-power-position-exploit-young-women-way-react-matters-even-today/

Gazette, 1998. India Present University with bronze bust of Mahatma Gandhi. Volume 28, Number 17, January 21. http://www.yorku.ca/yul/gazette/past/archive/012198.htm

Guha, R. 2018. Setting the Record Straight on Gandhi and Race, Wire, 23 December. https://thewire.in/history/setting-the-record-straight-on-gandhi-and-race

India-Senegal Relations. 2018. December. https://mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/Senegal_december_2018.pdf

India Times. 2016. India’s First Statue of Gandhi Killer Nathuram Godse Univeiled by Hindu Mahasaabha in Meerut. October 2. https://www.indiatimes.com/news/india/india-s-first-statue-of-gandhi-killer-nathuram-godse-unveiled-by-hindu-mahasabha-in-meerut-262820.html

Keynote Speech: 125th birth anniversary celebratory event for Dr. BR Ambedkar. http://laps.yorku.ca/about/message-from-the-dean/a-tribute-to-dr-br-ambedkar-on-his-125th-birth-anniversary/

Lal, Vinay. 2000. Nakedness, Nonviolence, and Brahmacharya: Gandhi’s Experiments in Celibate Sexuality, Journal of the History of Sexuality, 9, 1/2 (Jan-April), pp. 105-136.

Oke, Connor 2018. Why Students at Carleton University Are Trying to Have a Statue of Gandhi Removed, Vice, March 27. https://www.vice.com/en_ca/article/kzxb7e/why-students-at-carleton-university-are-trying-to-have-a-statue-of-gandhi-removed

Power, Marcus. 2019. Geopolitics and Development. New York: Routledge.

Vijayendra, T. (nd). “How Gandhi’s ‘Sexually Deviant” Behaviour Happened During His Worst Time in Politics,” YKA Youth Ki AwaaZ. https://www.youthkiawaaz.com/2016/07/gandhi-political-isolation/