In 1797, the Law Society of Upper Canada (since 2017 the Law Society of Ontario) was formed and three decades later it established Osgoode Hall as its home at the corner of University Avenue and Queen Street. The building was modest, located outside the municipal limits, and housed law courts and judicial offices and provided cramped quarters for students to “keep [judicial] term” or take the bar admissions examinations.

Osgoode Hall at University Avenue and Queen Street today

These were the beginnings of the Osgoode Hall Law School but it was not until 1889 that the Law Society made it a permanent institution. By this time, the building complex had been expanded into the Victorian Palace that it still is today. In 1969, however the law school was transferred to York University after the provincial government resolved that all law schools needed to be affiliated with a university.

Osgoode Hall Law School under construction in 1968. York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections, York University photograph collection, ASC01635.

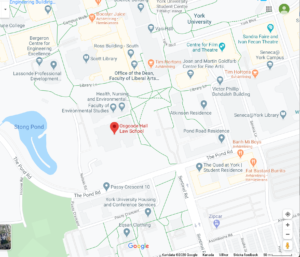

Ontario Heritage Foundation sign at Osgoode Hall

For close to two centuries, the complex of law buildings downtown, the law school at York, and a subway station, have carried the name Osgoode after the first Chief Justice in Upper Canada, William Osgoode, who served the colony from 1791 to 1794. Inside the Hall downtown, there is a memorial plaque acknowledging Osgoode, reading “William Osgoode. M.A. (Oxon) who when the Province of Upper Canada was organized in 1792 became its first Chief Justice and was afterwards Chief Justice of Lower Canada. Died in 17th January 1824 aged 70 and was buried at the Church of St. Mary at Harrow-on-the-Hill, London.” There are also plaques at the Hall by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada (inside) and the Ontario Heritage Foundation (outside) recognizing Osgoode.

But who was William Osgoode, and does his name represent these institutions well?

At the time of his appointment as Chief Justice of Upper Canada, Osgoode was well established in his profession. He received a classical education at a Methodist school in Kingswood, attended Oxford University for BA and MA degrees, entered Lincoln’s Inn in 1773, spent a year in France, and was called to the English bar in 1779. He also engaged in legal debates, publishing Remarks on the Law of Descent, a critique of Sir William Blackstone’s writings on English laws. This publication may have yielded him sufficient influence at Whitehall, the British civil service, to obtain the position as first Chief Justice of Upper Canada in 1791, with the promise of succeeding the ailing William Smith (1728-1793), who held the same but more prestigious position in Lower Canada. He was also successful in having his nominee, John White, appointed Attorney General. Once in Upper Canada, he was admired by a significant number of members of the colonial elite, among them politician, writer and merchant Richard Cartwright, with whom he shared a legal pragmatism and the vision of an Upper Canada settled by United Empire Loyalists who would serve as a bulwark against the threat of an invasion from the United States. Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe (1791-1796) did not share this conception, but was in favour of the recruitment of American emigrants. But Simcoe and Osgoode were otherwise on good terms. Simcoe even pressed Osgoode, before he parted for his position in Lower Canada, to remain long enough to write the Judicature Act of 1794, which established a superior court and laid the basis for the common law practice in Upper Canada. Osgoode was also part of passing legislation outlawing the importation of slaves into Upper Canada, but exempted the ownership and trade in slaves that existed at the time and that was common among the colonial elite (Therrien, 2020).

Osgoode was also a member of the Executive Council and served as Speaker of the Legislative Council. In these positions, he focused on how he could use the law to support the Crown, considering the courts as serving as “lions under the throne,” that is, coming out of their den to protect the King or Queen at a moment’s notice. Douglas Hay writes: “[Osgoode] made his reputation as an effective instrument of state power, at the expense of judicial impartiality … [he] was committed to upholding aristocratic, monarchical, anti-democratic government … [and] stood out as one of the fiercest defenders of British oligarchical government at the expense of the Rule of Law (cited in Baker, 2017: 760-1).”

His authoritarian tendencies were accentuated when he served as Chief Justice and member of the Executive Council and Speaker of the Legislative Council in Lower Canada from 1794 to 1801. When ceding Crown lands, Osgoode favoured freehold title, while paying no or little attention to “leading English case law that dealt with limitation on the reception of law in respect of ceded colonies or newly occupied Native lands (Baker, 2017: 766).” He himself benefited from such a policy, being an absentee landlord, owning twelve thousand acres of land in the Canadas, something facilitated by him being the long-serving chair of the Lower Canadian Executive Council’s Committee on Land Grants (Ibid.: 759). The Governors-in-Chief Robert Prescott (1796-1799) and Lieutenant-Governor Robert Shore-Milnes (1799-1808) never mentioned Osgoode’s role as an absentee landowner but did accuse him of being “vain and idle enough to act as the land speculators stalking horse on the Executive Council.”

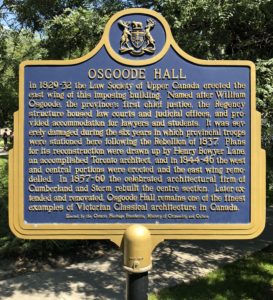

David McLane’s ghost is said to walk the streets of Quebec City, much to the thrill of the tourists. In the halls of Osgoode Hall Law School, he appears to be absent. https://www.amazon.com/Proc%C3%A8s-Trahison-Illustr%C3%A9-Soir%C3%A9es-Canadiennes-ebook/dp/B07H1HBY72

Osgoode’s authoritarian position was also reflected in his role as a justice, but on this point he likely had the support of the colonial elite. The case of high treason against an American, David McLane, alleged to have supported a French plot to undermine British rule, illustrates the means he and the courts used to seek a conviction. A couple of the major Crown witnesses illegally received generous gifts from the Crown and then lied about it in court. The two defense lawyers were young and highly inexperienced; one of them even lived with the Attorney General and also served as the lawyer for one of the compromised Crown witnesses. The jurors came mainly from the wealthy English elite with no Canadiens, an unusual situation. The indictment was trumped up, including the charge of plotting to kill the King, despite his residence being three thousand miles away. Finally, since McLane was an alien enemy, there was a valid case to make that he could not be charged for high treason, but his lawyers did not make this argument, nor did Osgoode bring it up. In the end, McLane was convicted and Osgoode sent him to be hanged and quartered, a sentence that was rare at the time, and largely phased out in Britain.

Osgoode appears to have become increasingly disillusioned with his stay in the Canadas. In 1801, at the age of 47, he offered to resign on the condition he receive a £800 pension. When his offer was accepted, he left Upper Canada to settle and live a fashionable life in retirement in London. He never returned to the Canadas. Besides his differences with the Governors, perhaps the colonies did not live up to his aristocratic ambitions. He came from a family of Methodist hosiers named Osgood but concealed that lineage by adding an “e” to his surname. To further distance himself from his origins, he chose, when relocating to London, to occupy the former residence of the Duke of York, Frederick Augustus. This gave rise to rumours that he may have been the illegitimate son of King George II, a rumour he may not have resented.

In 1824, he died and was buried at the Church of St. Mary, Harrow-on-the-Hill, an exclusive area of London. On a plaque at the Church, the text reads, “respected and beloved for integrity and talent: he had that which should accompany old age, honour, and troops of friends.” It was to these friends he bequeathed his considerable wealth, leaving nothing to his relatives.

When Osgoode Hall Law School travelled to York University, the journey was not easy. Many of the faculty at the downtown location resisted the move, the Dean resigned over it, and the Law Society opposed the Osgoode name being part of the “new” school at York. The new faculty members at York had to rally the support of the Board of Governors and a couple of prominent mediators to get the approval from the law society. It appears that the new law school desired the gloss of the Osgoode name to give it credibility and profile at its suburban location, while paying little attention to scrutinizing William Osgoode himself.

The Osgoode Hall Law School web page in 2020 prominently displays William Osgoode. The image of Osgoode is a copy of portrait by George Theodore Bertheon. The original hangs in Osgoode Hall.

The William Osgoode Society, a fund-raising organization for Osgoode Hall Law School, is still wedded to the memory of Upper Canada’s first Chief Justice.

Today, William Osgoode continues to be part of Osgoode Hall Law School’s branding efforts, most notably on its website but also in the shape of the William Osgoode Society, which “was established to honour Osgoode’s most generous donors … [and] named after the first Chief Justice of Upper Canada.” On its website, the Society lists all the donors “whose cumulative paid gifts total more than $25,000.” In the background, there is a portrait of Osgoode, where a very sympathetic-looking Chief Justice, with a faint smile, seems to thank the donors for supporting the law school that carries his name.

To be sure, William Osgoode ought to be understood and analyzed in the context of his time and location. A historical relativist perspective would suggest that he was a mere product of his time. Due to Canada’s “garrison mentality” at the time, and fearing an American invasion and a French-induced uprising in Lower Canada, Osgoode had to support authoritarian rule and, with McLane, for example, stipulate deterrence. Baker suggests that had Osgoode been criticized along the lines above, he would simply have shrugged his shoulders and said: “yes, but what, exactly, is irregular in what I have done? (Baker, 2017: 762).”

However, Osgoode also had choices. He was not a mere victim of historical circumstances but faced options and took decisions that could have been different even during his times, and that today do not reflect well on his profession. He clearly rejected an impartial judiciary; he was an authoritarian; he used his office to benefit himself materially; his anti-slavery stance was severely compromised; and he sought to fabricate an aristocratic image of himself that rejected and sought to conceal his true past.

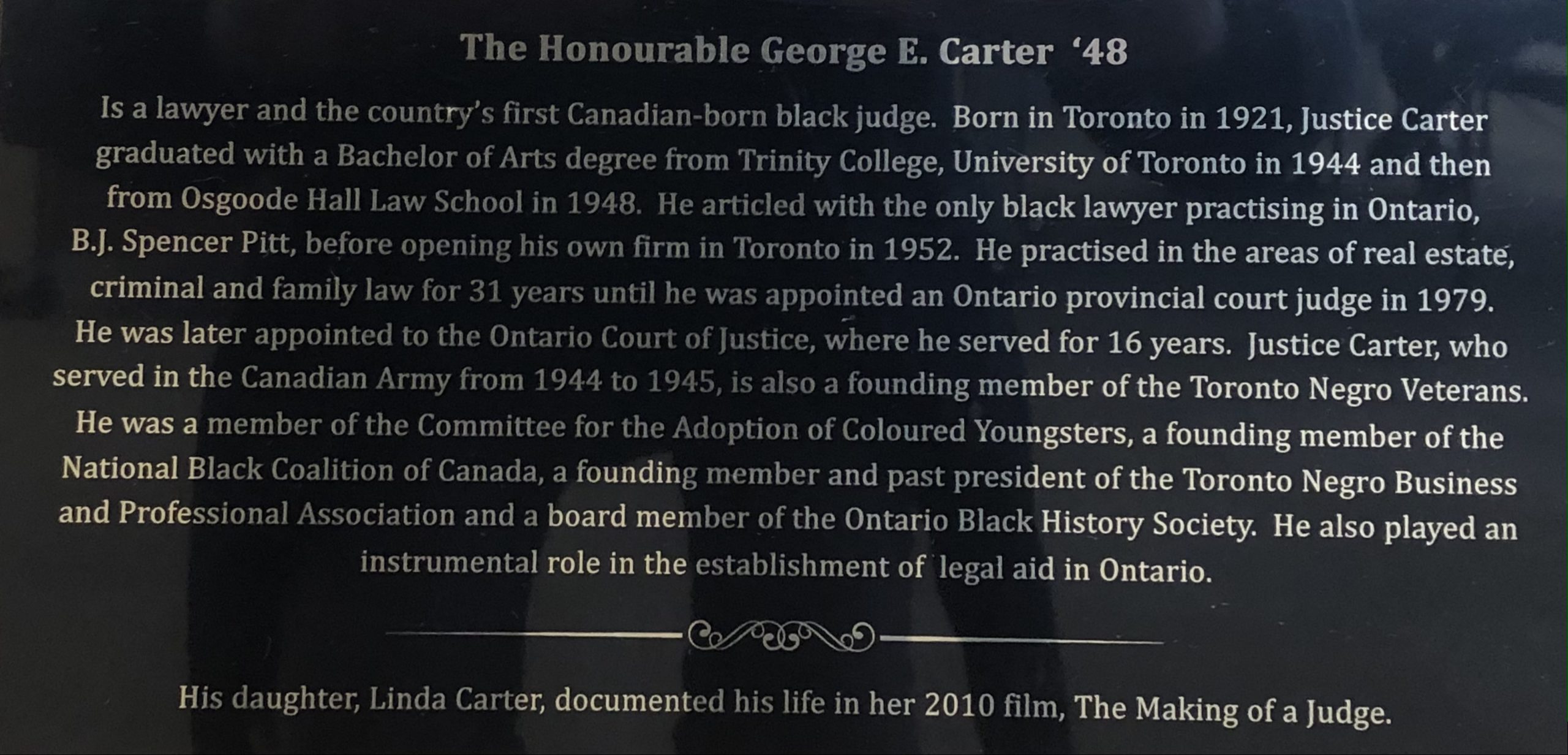

Should William Osgoode and his name still stand as institutional representations when the symbols and signs of imperialism and colonialism are increasingly questioned, removed, and replaced? Does his positive attributes outweigh his negative ones? Does his contributions to legal scholarship and practice warrant his present recognition? Do individuals at all warrant recognition? If so, are there better representatives than Osgoode? At one point, Lincoln Alexander who graduated from Osgoode in 1953, may have been a good candidate. He became Canada’s first Black Member of Parliament in 1968, the first federal Black Cabinet Minister in 1979, and then served as Ontario’s first Black Lieutenant-Governor. But the Toronto Metropolitan University beat York to it and adopted Alexanders’ name for its law school in 2021 (Ryerson Today, 2021). But there may be another worthy Black candidate, George E. Carter, who graduated from Osgoode in 1947. Born in Toronto in 1921, he became the first Black Canadian-born judge in 1979. He is memorialized in the Osgoode Library with a bust and a plaque that recites his many professional and community contributions.

George E. Carter displayed in Osgoode Hall Law School Library

George E. Carter plaque

Or why not Harry LaForme of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation who graduated from Osgoode in 1977 and who has served in many public positions, including Justice of the Ontario Court of Appeal, the first Indigenous person ever to sit on any appellate court in Canada. Carter and LaForme, I bet, will stand the test of time much better than Mr. Osgood, oops, pardon me, I meant Mr. Osgoode.

References:

Baker, G. Blaine 2017. Musings and Silences of Chief Justice William Osgoode: Digest Marginalia about the Reception of Imperial Law. Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 54, 3, 741-776.

Greenwood, F. Murray 1991. The Treason Trial and Execution of David McLane. Manitoba Law Journal, 20, 1, 3-14.

Jones, Donald 1993. Obscure lawyer who rose to greatness lends legal buildings home: The mystery of Chief Justice William Osgoode. Toronto Star, 1 May, p. J8.

Mealing, S.R. 2003. “OSGOODE, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed July 1, 2020, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/osgoode_william_6E.html.

Ryerson Today 2021. Ryerson renames Law School after the Honourable Lincoln Alexander. April 6.

Therrien, Gerald 2020. Simcoe fought against a slave revolt in Haiti. Toronto Star, 8 August, p. IN7.