Just to the south of York University, along Black Creek, in former farmers’ fields, in a utility corridor harbouring hydro towers, pipelines, and a recreational trail, there is an Ancestral Huron-Wendat village.1 It dates from the late fifteenth to mid-sixteenth century and it was at that time one of several similar villages in the Toronto area. Containing a population of up to fifteen hundred people in around forty to fifty long houses, the village was palisaded for defense purposes, and outside its perimeter the village people grew the Three Sisters, corn, squash, and beans. Archaeologists estimate that the farm fields extended in a one-kilometer radius beyond the village which means that large parts of York University sit in such fields. This includes my office and the areas that I walk on campus, something I think about almost every day when I am at York.

Paradoxically, the very same utility corridor that disturbs the village in some way also protects it. The village is better preserved than many other similar villages that were destroyed by housing subdivisions, or buried under roads, and other infrastructure. Some of these villages we probably don’t know about, others have been located and excavated to a varying extent by avocational and professional archaeologists and by looters and pothunters. Apart from the rare sign, there is very little to tell that these villages were once thriving and lively communities.

The village at York University is called the Parsons Site after the farm family who owned the land at the time of its formal discovery by archaeologists in the early 1950s. This is a common practice for other archaeological sites. The Parsons Site also has a letter and number name, AkGv-8, which is part of a uniform site designation scheme for archaeological sites in Canada. These names both reveal and conceal. The word Parsons obscures the Huron-Wendat past and the archaeological designation and the word “site” reduces the village to a place of dead “artefacts” and “human remains.” At a few village locations, the Huron-Wendat have changed their names, the most prominent being the Mantle Site in Whitchurch-Stouffville which is now known as the Jean-Baptiste Lainé Site after a Huron-Wendat World War Two veteran.

But the obscuring of the Huron-Wendat goes beyond the naming of their old villages. There are unique ways in which the Huron-Wendat presence is absent both in Ontario generally and on the York University campus specifically.

One of the reasons for the lack of recognition of the Huron-Wendat in Ontario generally is that they moved from the Toronto region in the face of attacks by the Haudenosaunee in the early seventeenth century. They first moved to Wendake or Huronia, an area between Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay, only to relocate again to settle in Oklahoma, Michigan, Kansas and Quebec, and scattered locations in Ontario, especially the Windsor and Toronto areas, where they still live. For settlers and even some Indigenous people, the Huron-Wendat’s move from the region is often interpreted as a permanent one, which renders them absent in the region. Nothing can be further from the truth. The Huron-Wendat still harbour vital and vibrant communities with a deep consciousness of their past. A past post-doctoral fellow at the York University Department of History, Kathryn Magee Labelle, has written two excellent books, one in collaboration with the Wendat/Wandat Women’s Advisory Council, whose titles speak clearly to these connections, Dispersed but Not Destroyed: A History of the Seventeenth Century Wendat People (2013) and Daughters of Aataentsic: Life Stories from Seven Generations (2021). Today, the Wendat and Wyandot(te) live in four different nations that go under different names: the Huron-Wendat Nation of Wendake in Québec; the Wyandot of Anderdon Nation in Michigan; the Wyandot Nation of Kansas; and the Wyandotte Nation, in Oklahoma. Wendat and Wyandot people are also present in Ontario. Collectively, the Wendat number approximately 10,000. They are all connected through the Wendat Confederacy. Of the four nations, the Huron-Wendat of Quebec are the spokespeople for their heritage in Ontario and leading the efforts to connect and protect the remains and sites of their Ancestors in the Toronto region.

"Ora8an": SunFlower" by © CatherineTammaro 2021 used with permission. The sunflower shines a light on the continuous presence of the Wyandot in Ontario. It is here depicted in the artwork of Catherine Tammaro, Small Turtle Clan FaithKeeper,

Wyandot of Anderdon Nation, who was born in, and lives in Toronto. The Huron-Wendat grew sunflowers for their oil, using it in food and as a body rub, customarily oiling a person’s scalp in greeting, respect and to calm their mind. See http://www.saintemarieamongthehurons.on.ca/sm/en/HistoricalInformation/TheLifeoftheWendat/index.htm and Victoria Jackson, “Children and Childhood in Wendat Society 1600-1700,” Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of History, York University, 2020, 58n.

In popular culture, the absence of the Huron-Wendat can surface in school textbooks where they are portrayed as a vanished people. Among archaeologists, the absence of the Huron-Wendat is often explained by the confusion between the terms Iroquois and Iroquoian. The term Iroquois refers to the Haudenosaunee or the Six Nations Confederacy whose homeland was in central New York State but a segment of whom settled on the Grand River in connection with the Haldimand Treaty of 1784. The term Iroquoian, on the other hand, refers to Iroquoian-speaking Indigenous groups that include the Haudenosaunee, Huron-Wendat, and Cherokee, though these groups are very distinct and the Huron-Wendat and Haudenosaunee have, at times, been enemies. The similarity between the two terms has meant that ancient sites that are Huron-Wendat have been identified and labeled as Iroquois or Haudenosaunee, though no such confusion or conflation has occurred with Cherokee sites. Perhaps the most famous site is the Huron-Wendat ossuary (burial site) named Taber or Tabor Hill in Scarborough that was discovered in the mid-1950s. At the time, it attracted wide attention throughout North America (with a feature in Life Magazine) but it was identified as attached to and then celebrated by the Haudenosaunee from Six Nations. The ossuary, though now definitely identified as Huron-Wendat, is still labeled Iroquois on a sign and plaque posted at the site, and there is also a Six Nations Avenue nearby. Until the late 1990s, the former Ontario Cemeteries Act furthered the absence of the Huron-Wendat by allowing the nearest First Nations group to approve the retrieval of human remains rather than the groups that were culturally connected to the dead.

I wonder about these interpretations. Many archaeologists have known to distinguish between Haudenosaunee and Huron-Wendat settlements and ossuaries for a long time, and some Huron-Wendat have taken part in archaeological digs of their Ancestral villages since the 1970s, yet the “confusion” persists. Could it be, rather, that archaeologists, whose primary pursuit, after all, is to excavate and “unearth” may have found it more convenient to consult with “Iroquois” and “the nearest First Nation group” rather than take the time and effort to consult with the Huron-Wendat in faraway Quebec.

The absence of the Huron-Wendat has been fuelled by the assertion of jurisdiction over land by other Indigenous groups in the Toronto region, assertions where the resident Indigenous groups, the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe have had the distinct upper hand. The Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation are, of course, the current treaty holders of the lands that occupy York University, though other Anishinaabe groups consider the lands as their traditional territories too. The Haudenaosaunee claim the land through the Nanfan Treaty of 1701 (though Nanfan does not extend that far westward) and some of the provisions of the Haldimand Treaty of 1784. The Huron-Wendat, by contrast, do not assert any claims on land, though they are adamant about protecting and caring for their Ancestral village sites. Metis scholar Jesse Thistle describes the ensuing tension as follows:

‘Haudenosaunee people, some of them, don’t want to recognize that the Anishinabe took control and were here historically. Some Anishinabe people will not recognize that the Haudenosaunee people were here. And both those people sometimes want to erase the Wendat.’ Historical truth is always subject to the structures of power. Always. The erasure of the Wendat ‘is, in a way, a kind of indigenous way of doing what the British were doing, in terms of writing other people out of the narrative,’…(quoted in Marche, 2017).

At York University, you need not go far from the Huron-Wendat village to notice examples of the erasures that Thistle refers to. A few hundred metres north of the village, York University has a community garden called Maloca Garden. Maloca is the name for the long houses used by Indigenous peoples of the Amazon rainforest, in particular Brazil and Bolivia. The people who came up with the Maloca name are unlikely to have known about the presence of the Ancestral Huron-Wendat village, but it now represents an opportunity to recognize the presence of the Huron-Wendat, their long houses and village at the garden and in the geography of the campus.

Maloca Garden. Maloca is the name for the long houses of the Indigenous peoples of the Amazon rainforest. The name sadly ignores the longhouses of the Huron-Wendat only a couple of stone throws to the south.

At the York University campus itself, despite the Huron-Wendat being mentioned in its land acknowledgement as one of the three Indigenous groups holding the university lands as their “traditional territory,” there are few signs of a Huron-Wendat presence. On the positive side, the Centre for Aboriginal Students Services now includes the Wendat greeting word “Kwe” among its other Indigenous language greetings, many of them with no historical connection to the area, though it only happened a few years ago. And yes, the Glendon Campus hired a Huron-Wendat faculty member, Yann Allard-Tremblay, in 2017, an active member on York’s Indigenous Council, though they left in 2020 for an appointment at McGill University.

Yet there are also absences. Skennen’kó:wa Gamig is the name of a small house and dedicated space for gathering, learning, and ceremony for Indigenous students, faculty and staff. The two words in the name of the house, the House of Great Peace, honour the “Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe presence and traditional territory in Toronto, and is in keeping with the Dish with One Spoon Wampum treaty, an agreement originally made among Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe nations to peaceably share the lands of the Great Lakes region.” But the name leaves out the Huron-Wendat while it could, potentially, given its name, honour the “Great Peace” of Montreal in 1701, the first peace agreement between Indigenous groups (including the Haudenosaunee, Anishinaabe and Huron-Wendat and many more) in North America that was orchestrated by the French. The Huron-Wendat Chief Kondiaronk, who is widely celebrated in Quebec and beyond, was the principal actor in achieving the Peace Treaty.

Skennen’kó:wa Gamig. A Campus venue for Indigenous faculty, staff and students. The name acknowledges the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe but not the Huron-Wendat.

The Seneca College branch on the campus similarly erases the presence of the Huron-Wendat. Though there are various accounts of the origins of the College’s name, the College’s official history states that it was Norn Garriock, a Director of Television for the CBC and later second Chair of the Seneca College Board of Governors, who recommended the name. Mr. Garriock was inspired to suggest the name by an archaeological village site in Woodbridge, the McKenzie-Woodbridge Site (AkGv-2), where he lived and was councilor and reeve. Garriock mistakenly thought that the village was a Seneca site, the Seneca being one of the Haudenosaunee Six Nations. Perhaps he was confused by the Seneca Heights subdivision that was established at the site in the 1950s. In fact, the archaeological site is Ancestral Huron-Wendat, something that archaeologists have known since the 1950s. Seneca College is, then, misnamed, but on the York Campus the situation is made worse by the College’s branch campus sitting in a Huron-Wendat Three Sisters farm field.

Seneca College has a branch at the York University Campus. There is no evidence of the Seneca occupying the campus.

Across the campus, there are many examples of Indigenous art, including a spectacular statue, Ahqahizu, done by Inuit sculptors Ruben Komangapik and Koomuatuk (Kuzy) Curley, in celebration of the North American Indigenous Games held on campus in 2017. There are also art pieces by Cree, Anishinaabe, Métis, and Gitxsan artists on campus. A recent art project honours a Mi’gmaq artist. These are worthy projects in themselves but they also call attention to the Huron-Wendat absence on the campus.

Ahqahizu, an Inuit statue on campus. Unfortunately, there are no symbols celebrating the Huron-Wendat past on campus.

In spite of their present absence on the campus, the Huron-Wendat still insist that they are very much alive and that they have a deep connection to their Ancestral villages and ossuaries in Ontario, which they refer to as Wendake South.

The Huron-Wendat still see their Ancestral village south of the campus as a living and important part of their heritage. Since the late 1990s, the Huron-Wendat in Quebec, whose homeland is Nionwentsïo, have taken the lead to protect their heritage in Wendake South. Backed by their own activism, on the ground vigilance in tracking development projects, and court battles, the Huron-Wendat have repatriated or rematriated human remains from museums and archives which they have buried at key sites as well as asserted control and recognition of many Ancestral villages and ossuaries across Wendake South. A team of Huron-Wendat visits the province on a regular basis, and they also have Huron-Wendat members stationed at archaeological sites throughout the province. There are continuous discoveries of Huron-Wendat material and Ancestors found as development proceeds across the province.

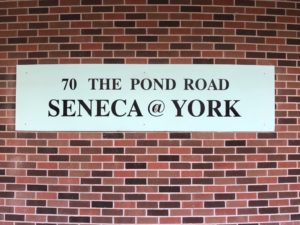

In 2013, the Huron-Wendat were part of the Shared Path initiative, an effort by various Toronto institutions (though not YorkU) and Indigenous groups to recognize the Indigenous heritage of the Toronto region. As part of that effort the recreational trail along the hydro corridor south of the campus is named the Huron-Wendat Trail. Along the trail, there are four plaques celebrating their presence, How Earth Was Formed, Parsons Site, Toronto’s Huron-Wendat Heritage, and Transforming Village Life. The plaques are located some distance from the village, two at Sentinel Road and Murray Hill Parkway and the other two west of Black Creek. This is in order to avoid any potential looting of potential desecration of the village itself, which is located on the east side of Black Creek. There are also copies of the plaques hanging in the offices of the Nionwentsïo Research team in Wendake.

One of the four plaques commemorating the presence of an Ancestral Huron-Wendat village south of the campus.

When unveiled, the Grand Chief of the Huron-Wendat, Konrad Sioui, was present, Mayor Ford announced a Huron-Wendat day in Toronto, and archaeologist Ron Williamson led a bike tour along the trail and at the village location. There were no York University representatives present. The plaques, however, are confined to an account of the Huron-Wendat as a people of the past, there being no indication that they are still alive in the present.

A delegation of Huron-Wendat Nation attending the opening of the Huron-Wendat trail south of the campus in 2013. Photo courtesy Ron Williamson.

York University’s engagement with the Huron-Wendat village is limited. The Alternative Campus Tour takes students there on a regular basis and the site has also been part of some of the annual Jane’s Walks (see also Peace, 2010). Through the work on the Tour, an effort has also been launched to locate a massive archaeological collection gathered by an amateur archaeologist, John Morrison, at the site during the 1950s to the early 1970s, and then again for a few years in the late 1970s to early 1980s. When Morrison died in 2001, part of his collection was lost and part of it went missing. One of Morrison’s relatives has since passed on some of the items of the collection to the Huron-Wendat who will eventually display them at their museum in Wendake.

A bone arrowhead retrieved by John Morrison. Courtesy of the Huron-Wendat Nation; photograph by John Howarth

The Alternative Campus Tour has also inspired an academic article on the village site in collaboration with the Huron-Wendat (Sandberg et al., 2021). It may, at some time in the future, set the stage for a wider and deeper engagement with the Ancestral village, led by the Huron-Wendat, at their pace, and on their terms, but hopefully supported by the academic community at York University, their neighbours, and other interested parties.

Endnote

- Following Catherine Tammaro, I capitalize Ancestors and Ancestral because the terms refer “…to a particular group of people who are spiritually present in the memory of the land.”

References

Marche, Stephen (2017). "Canada's Impossible Acknowledgement," The New Yorker, 7 September.

Sandberg, L.A., J. Johnson, R. Gualtieri, and L. Lesage (2021). “Reconnecting with a Historical Site: On Narrative and the Huron-Wendat Ancestral Village at York University, Toronto, Canada,” Ontario History, CXIII (1), 80-105.

Peace, T. (2010). “500 Years of Building Communities and Changing Environments.” https://blackcreekwalk.wordpress.com/500-years-of-building-communities-and-changing-environments/