On March 3, 2024, CUPE 3903 at York University went on strike, fighting for wages that keep up with inflation and in defence of hard-earned gains made in working conditions in the past. CUPE 3903, which stands for the Canadian Union of Public Employees Local 3903, represents Teaching Assistants and part-time Instructors on campus. On March 6, 2024, I visited the picket line at the main entrance of the university at Keele Street on York Boulevard. It was well attended and this time union leaders from across the province were there to lend support. The speeches were loud and rousing, the reception enthusiastic, and I imagined that the cheers might have reached the Kaneff Tower in the distance, where the President and Provost have their offices.

CUPE 3903 strike rally on March 3, 2024

I spent a couple of hours on the line and looked around, spoke to the strikers a little, and reminisced about previous strikes at the site. I also checked out a university billboard at the entrance. It is securely fastened to the ground with four wooden pillars buried in cement foundations and carries advertising messages of the university that change from time to time. It now reads RIGHT THE FUTURE beside a photo of the big blue earth with the additional message “Join us in creating positive change by building collaborative partnerships.” It rang poignantly hollow in view of the picketers gathered in the background. The message also rang hollow in light of my own presence on the picket line. This is because the Administration have insisted that faculty members continue teaching their courses without Teaching Assistants, a situation that many professors not only feel would compromise academic integrity, work against past practice, and complicate the remediation period that will follow the strike, but also constitute a form of strike-breaking.

The laudatory advertising messages about “building collaborative relationships” betray a hardening stand of the University administration towards its workers.

The labour movement has always figured as an important component of my life. I came of age in the industrial city of Eskilstuna in social democratic Sweden in the 1960s and 1970s. I grew up with an understanding of the importance of collective bargaining and right to strike and picket. When first implemented in Sweden in the late 1930s, it was not only a gain for labour but a compromise that yielded many benefits to employers. The Communist Party of Sweden labeled collective bargaining “handcuffs for Christmas” because workers had to commit to long-term contracts and regulations during which strikes were illegal. Employers thereby benefited from long periods of “peace” on the labour market and could “prepare” themselves for potential strike actions after a contract had expired. But during the occasions when strikes and picketing were legal, governments, employers and workers saw them as legitimate and respected institutions integral to the collective bargaining process. The current situation at my University seems to reverse that situation. Some refer to it as concessionary rather than collective bargaining.

The signs, symbols and struggles of work, working class people, and the history of the labour movement and its unions surrounded me when I grew up, as they still do today when I go there to visit. In the middle of the city square, there is a circular fountain entitled The Honour and Joy of Work, depicting working people’s life in the every-day, including birth, death, work and recreation. The symbol of the city itself is a couple of blacksmiths working at an anvil, and in the People’s Park (Folkets Park), there are busts of famous labour leaders and a memorial to the great national strike of 1909.

I often think about and contemplate the campus through the lens of labour. But when I walk the picket line under the current strike, I see very few signs of labour’s past struggles on the campus. This in fact applies to the grounds of the campus more generally, a place I have worked at for almost thirty years. I can only think of a very few signs in honour or in memory of labour on the campus, be it faculty, staff or student labour or the workers responsible for constructing the general campus infrastructure, such as buildings, roads, and the subway. This is in spite of my University advertising itself as the social justice university as well as being seen as a place of considerable and frequent labour “unrest.”

For some time, I have contemplated doing an Alternative Campus Tour looking for the signs of labour on campus. This now seems an opportune moment during another strike. But I also realize the limitations of such a quest. The following should therefore be seen as a combination of notes and observations that are personal and incomplete but perhaps inspiring for future documentations and initiatives to enhance the visibility of labour’s presence on campus.

It was in the spirit of looking for symbols and celebration of labour on campus that I visited the CUPE 3903’s Big Gay Garden a sunny day in early September 2018. The garden was started on May 7 during CUPE’s previous strike that began on March 5 the same year and lasted for 143 days til July 25. It was located near the picket line at the same site I visited in 2024. The issues of the strike revolved around job security for contract faculty, funding protection for teaching assistants, and workplace accessibility and equity. Few of the issues were resolved and the strikers were legislated back to work by a newly elected Progressive Conservative government. In the aftermath of the strike, the union requested that the Garden be maintained, but the University drew a hard line and insisted the Garden be eliminated. Its symbolic value clearly mattered. One gets a sense of this from one of the University’s letters sent out to the community, charging the union with regrettable behaviour, including “destroying University property” which, it claimed, involved “digging a garden near the York Boulevard.”

CUPE’s 3903 Big Gay Garden in 2018. Did it destroy or improve University property?

When I observed the Garden, however, I sensed no sign of destruction of property. Instead, I noticed tender signs of love and affection in an otherwise sterile lawn landscape. Cherry tomatoes grew there, as did bright orange marigolds, yellow daisies, different coloured pansies and various food plants, among them some purple kale.

Cherry tomatoes growing at the Big Gay Garden.

Orange marigolds growing in the CUPE 3903’s Big Gay Garden. Marigolds repel deer and rabbits who find their smell offensive. University administrators also find Marigolds offensive, but for different reasons.

On September 21, 2018, CUPE 3903 held a Respectfest at the garden, harvesting some of the produce, but also countering the efforts on the part of the York University Administration to penalize some of the student activists who had, allegedly, acted “disrespectfully” during the strike.

Welcome sign to CUPE 3903’s Big Gay Garden.

The Big Gay Garden gone in 2019 though its borders are still visible on the ground. Is the garden merely sleeping and will it awaken one day? Why did it have to be taken out in the first place? What harm did it cause?

When I returned to the Garden a year later, in early September, 2019, it was gone. This time, the huge university billboard that towered in the background carried a different message. On it, huge white bold letters declared THIS IS IMPACT over an image of the earth with lines criss-crossing it. In smaller letters, the sign stated that York is “preparing engaged global citizens,” citizens that travel along the lines on the map I suppose. I wondered, though, for whom and by whom that IMPACT would have been, and that it was too bad that it took place at the expense of engaged local citizens, including the members of CUPE 3903 who built the Big Gay Garden only a few meters away.

In the efforts to attract students, universities advertise themselves and York is no exception. In this instance, students are alleged to have impact on the world once they graduate. There is less attention paid to the impact university policies have on its workers.

If you venture beyond the picket line on University Boulevard and Keele Street, there are some signs of labour on campus, though they are not plentiful. One prominent person that has figured in a labour struggle and who is celebrated on campus, is Harry Crowe. He has given name to the Harry Crowe Room (109 Atkinson College) and Harry Sherman Crowe Housing Co-op.

Sign of the Harry Crow Room in Atkinson.

The housing co-op was one of the last built in Toronto in the 1990s and it was the result of the efforts of the labour unions at the university. There are no signs or plaques, however, that tell this story, nor any information on who Harry Crowe was and his significance in the history of academic labour. But it is easy enough to find out. Crowe was a Professor who was fired by United College (now the University of Winnipeg) in 1958 as a result of a private letter he had sent to a colleague in which he expressed concerns about the religious and academic climate at the College and the prospects of a Conservative win in the pending federal election (June 10, 1957). Crowe’s colleague never received the letter. Instead, it mysteriously ended up in the hands of the President of United College who felt Crowe’s views somehow compromised the College’s position and he was let go. It is outrageous that a faculty member’s private letter could end up in the hands of a University President, but it is interesting to contemplate that is even easier today for University Administrators to monitor faculty members correspondences, especially emails, to which they have legal access. My own union now recommends that faculty members use non-university emails for correspondence on sensitive work-place matters.

The entrance to the Harry Sherman Crowe Housing Co-op on Chimneystack Road. There is currently an Affordable Housing Committee at York that is promoting the building of affordable housing on campus.

Crowe’s dismissal triggered several resignations of faculty members at the College who were sympathetic to Crowe. It also prompted the Canadian Association of University Teachers to form an ad hoc committee of enquiry into the dismissal. The enquiry found that the College had violated natural justice, due process, and academic freedom. It is likely that the enquiry influenced the College’s decision to offer to reinstate Crowe. The College did not, however, offer reinstatements to the colleagues who had supported Crowe, which triggered twelve more protest resignations.

One of the major legacies of the Crowe incident was the formation of the Academic Freedom and Tenure Committee of the Canadian Association of University Teachers that to this very day monitors and investigates freedom matters for academic staff in Canada. Crowe went on to become a Professor (1966-9) and College Dean (1969-1974 and 1979-1981) at York University, as did one of his supporters, Geography Professor John Warkentin. Another supporter, William Packer, a Professor of German at the University of Toronto, along with his wife, Katherine Packer, a librarian at Glendon College and York University, established a K.H. and W.A. Packer Endowment in Social Justice. The Endowment sponsors a Visiting Chair in Social Justice at York. Past chairs include former Ontario Coalition Against Poverty organizer John Clarke, former Canadian Auto Workers’ Research Director Sam Gindin, former Canadian Labour Congress Chief Economist Andrew Jackson, and social justice lawyer Fay Faraday, who is now a faculty member at York’s Osgoode Hall Law School.

Harry Crowe pictured among other Deans in the Harry Crowe Room

The Harry Crowe Room is perhaps appropriately located in the Atkinson Building named after another “labour” figure on campus. The Atkinson Building used to house the Atkinson Faculty of Liberal and Professional Studies. It opened its doors in 1962 to cater toward part-time students who had to attend school at nights or who could not afford to take a full course load. In 2009, the Faculty was closed and merged into a mega-faculty now entitled the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Professional studies. Faculty member James Laxer wrote about the centrality of accessibility to Atkinson, catering to working people who aspired to combine work and study in their lives and to poor students who needed to work part-time in order to sustain their studies. As a result, Atkinson students brought their life experiences to class, a situation that brought excitement to courses and challenged faculty members to do their best (Laxer 2019). The Harry Crowe Room contains several archival photos depicting dignitaries, politicians and students at convocations and at the celebratory openings of new buildings. There is also a photo showing all the Deans of Atkinson College from 1963 to 2001, including Harry Crowe. But I am looking in vain for a memorial to the Harry Crow affair at United College, a seminal event in the history of freedom of speech for faculty labour at Canadian universities.

All things Atkinson at York are named after Joseph E. Atkinson who rose from humble origins to become and remain editor of the Toronto Star from 1899 until his death in 1948 (Atkinson Foundation 2007).

The Atkinson Building, named after a friend of labour, Joseph E. Atkinson, the editor of the Toronto Star.

CUPE 3903’s offices, empty on March 28, 2024, as the union is on strike. The location of the offices, in the Atkinson Building, named after a friend of labour, may be appropriate though tragic given the current lack of respect for labour at the University.

Atkinson never forgot his roots and became an outspoken critic of governments for their neglect of the appalling social conditions in Toronto in the early 20th century. He and the Toronto Star became defenders and spokes organs for workers and argued in favour of trade unions. He was also a champion for the modern equivalents of welfare, old age pensions, unemployment and health care provisions. The Toronto Star was for a while distributed free on campus, perhaps a legacy of the connection between a social justice-oriented university with a considered, so far at least, progressive newspaper. At York’s Schulich School of Business, by contrast, The National Post, a business newspaper, was for a time distributed freely.

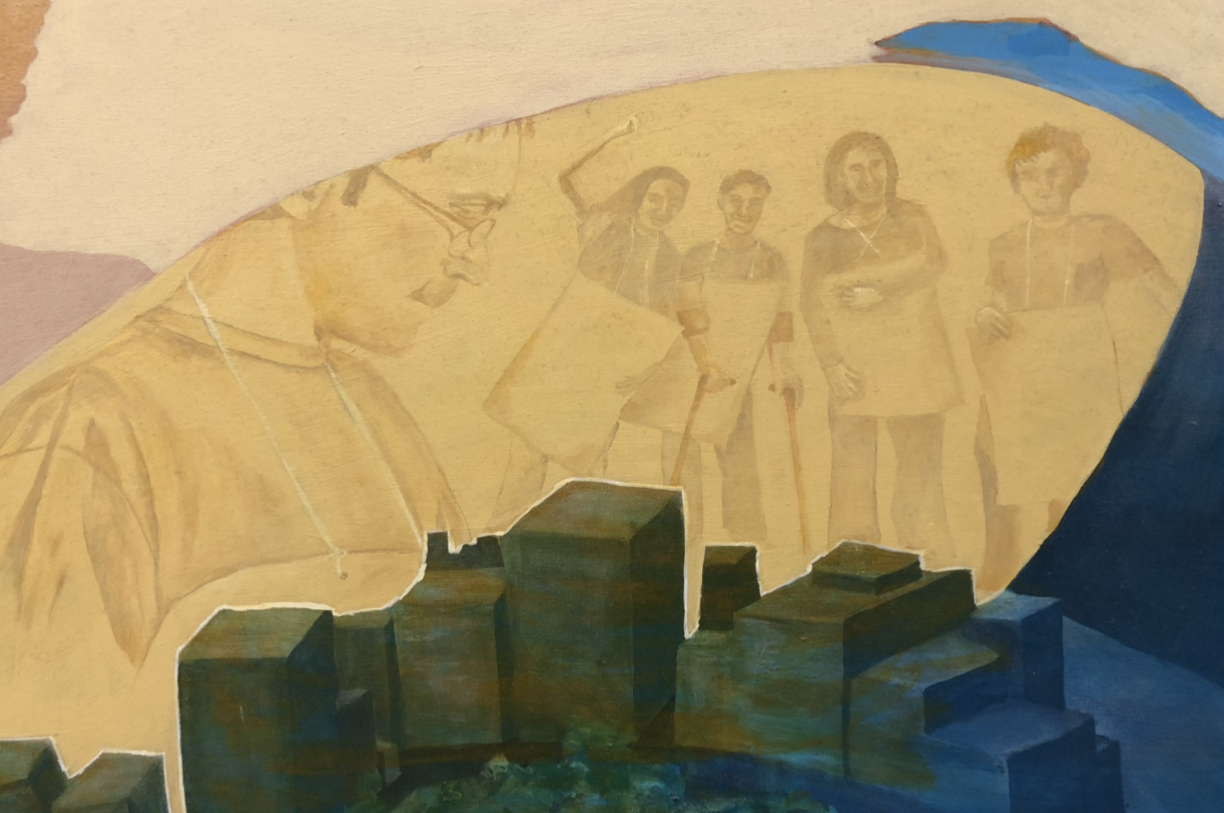

At Seneca College’s branch on the York University Campus, there is an interesting set of photos by conceptual artists Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge, who have collaborated with trade unions on staged photographic work over the last thirty years. In the photos, the artists illustrate the beginnings of the trade union movement at the General Motors automobile plant in Oshawa in the 1920s and 1930s. The photos describe the high-handed actions of management in opposing the union and in hiring workers. In one photo on the unionization drive, the text reads: “The Company knew something was going on. They had spotters. Damn it, if they saw three or four workers standing on the street corner, it was right back to the main office the next day.” They also describe how workers were hired every year in late December until late May. This left workers vulnerable when the employer hired them at the end of the year. One text in a photo recounts: “This is how they kept their jobs, you see: they did anything for the foremen; shovel their sidewalk, come in with a basket of vegetables, or a bottle all the rest, just to keep their jobs.” This is something that unions have fought to correct, using, for example, the seniority principle, prior experience, and qualifications, when hiring and firing workers, a condition that prevails in the hiring of part-time workers in CUPE 3903 but that the University now wants to replace with an arbitrary and subjective selection method on who would teach in a contractual faculty position.

In the lobby of the Health Nursing and Environmental Studies Building, where I have my office, we harbour a mural, named Gesundheit (in German health), that pays tribute to the three programs in the building. One of the details of the mural contains a rare acknowledgement to the labour struggles on campus, a picket line of one of CUPE 3903’s strikes on campus. I once heard a professor at a meeting reference a parent who had spoken up in appreciation of the labour militancy at York, indicating it had been a positive in her daughter's choice of university. The detail is a reflection of that sentiment.

Detail of labour struggle in the mural Gesundheit in the HNES Building.

Workers sometimes pay the ultimate price while on the job and they are sometimes remembered for it. At York University, one such event occurred when a 24-year-old crane apprentice, Kyle Knox, was killed when a drill rig collapsed in the process of building the York University subway station. Both the contractor and subcontractor, who plead guilty, were convicted and fined $400,000 and $50,000, respectively. The investigation that ensued delayed the building of the station substantially. It found that “major factors in the tipping of the drill rig were inadequate site preparation, a soil base unable to withstand the weight and pressure created by the drill rig combined with a procedure of digging dispersal holes filled with wet material, and the fact the drill rig was operating on a slope greater than allowed within safe parameters” (IUOE Local 793 2014). As a consequence of the Knox’s death, his union, Local 793 of the International Union of Operating Engineers, lobbied the government to legislate mandatory training for rotary drill rig operators, a practice the government introduced in 2015 (Cision 2015).

In the aftermath, a temporary memorial was erected at the site, on the south side of the Lorna R. Marsden Honour Court & Welcome Centre but it is now gone. I only managed to take a photo of a remnant piece of the memorial. Perhaps it is symbolic of the poor attention given to such tragic events.

There is, though, a memorial to Knox in the York University subway station. I walk by it twice every day when I travel to and from York on the subway.

Memorial Plaque for Kyle James Knox in the York University Subway Station. Note the use of the term “accident.” The inquest into the death suggests that it was something more than a mere accident. According to one source, eighty percent of all workplace accidents “are ultimately caused by improper precautionary measures” (Aftermath 2024).

In honour of Knox, Local 793 established the Kyle Knox Memorial Award, given periodically to members who exhibit extraordinary bravery and initiative in rescuing another member, fellow workers or a member of the public in a calamity.

On June 28, 2021, another worker, a supervisor, died in an industrial accident at the building of the Continuing Studies Building at York University, when a crane lost a large pane of glass at considerable height which then impacted the supervisor (Tsekouras, 2021). Stouffville Glass, a subcontractor was fined $150,000 for the incident after it plead guilty in Provincial Offences Court. An investigation of the Ministry of Labour, Immigration, Training and Skills Development “determined that taglines used to control the motion of the panel of the crane were not attached to the load, but instead were attached to a power grip used to hoist the load” (OHS Canada, 2023).

When asked about such industrial “accidents”, spokespersons for York University and the TTC (in Knox’s case) announce that they are not responsible, it is the responsibility of their contractors and sub-constructors.

There are no doubt other connections at York University to the labour movement and its struggles. There are also many scholars and students who pursue labour studies and teaching and research programs that focus on labour, including an interdisciplinary program entitled Work & Labour Studies and a research unit called the Global Labour Research Centre (Global Labour Research Centre. n.d.). Osgoode Hall Law School also offers a Certificate in Labour Law.

There are few signs of honouring labour or providing a record of past labour struggles on the York University campus, though such struggles are significant and relatively numerous. When strikes occur, there are temporary signs of labour struggles that crop up. The campus is then transformed into a battleground where picket lines, strikers, journalists, security guards, and police jostle for position and attention. And to be sure, these are signs that live on in people’s memories, but there are few signs left in the physical landscape. And it does not only apply to the Big Gay Garden.

I was part of a group of faculty union members planting a tree at the Northwest Gate in memory of eight long weeks walking the picket line in 1997. But, apparently, as I remember it, we planted the tree on the “wrong” side of a fence, and it was subsequently moved by the University to the “right” side of the fence. I confirm this by looking at a photo of the planting ceremony in 1997 that shows the tree planted close to the curb of the road. In 2007, according to google maps, it is no longer there, supposedly having been re-planted behind the fence. But when I now go and look for it, it is either gone or lost among the many other trees that have since been planted by the University, on both the “right” and “wrong” side, of the fence.

Faculty members planting tree in memory of their 8-week strike in 1997. Photo credit Deborah Barndt

There is no doubt other such signs that have disappeared or remain unattributed but live on in the memory of people. But few of these signs remain after the strikes are over and after the picket lines come down.

Why are there so few symbols and memorials to labour, be it faculty, students or staff, at York University, and more generally, at most other university campuses? In comparison, there are lots of memorials and names of buildings that honour the employer, the University Administration, and institutions and individuals associated with their positions. In the past, these were typically Presidents and Deans, and individuals with successful military, public and private careers, sometimes associated with the university, but lately more often represented by men (and sometimes their wives) of financial means who bestow large amounts of money to the university in exchange for tax receipts and lending their names to buildings and faculties.

Perhaps a wider recognition and appreciation of working people in the symbols and signs of the University might lead to a more balanced and respectful relationship and dialogue between its administration and workers. At least, I hope, it could be a beginning.

References:

Aftermath 2024. The Truth About Industrial Accidents. https://www.aftermath.com/content/industrial-accidents/

Atkinson Foundation. 2007. Fighting Words: The Social Crusades of Joseph E. Atkinson. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Injo_Fc1cE

Buckshon, Mark 2019. Inquest to review Toronto construction worker’s death more than nine years after the event, Ontario Construction Report, March 12. https://ontarioconstructionreport.com/inquest-to-review-toronto-construction-workers-death-more-than-nine-years-after-the-event/

Cision 2015. Mandatory Training for Drill Rig Operators Will Save Lives. December 9.https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/mandatory-training-for-drill-rig-operators-will-save-lives-561249101.html

CUPE 3903. 2018. YorkU new community garden. https://twitter.com/rankandfile3903/status/993668570952404993

Global Labour Research Centre. n.d.. https://www.yorku.ca/research/glrc/about/

IUOE Local 793. 2014. $400,000 Fine in Drill Rig Accident Is Not Enough: Local 793 Business Manager. November 28. https://iuoelocal793.org/400000-fine-in-drill-rig-accident-is-not-enough-local-793-business-manager/

Laxer, James. 2009. A Farewell to Atkinson College. Rabble.ca Blogs. June 30. https://rabble.ca/blogs/bloggers/james-laxer/2009/06/farewell-atkinson-college

OHS 2023. Glass contractor fined $150,000 after supervisor killed during construction at York University. November 30. https://www.ohscanada.com/glass-contractor-fined-150000-after-supervisor-killed-during-construction-at-york-university/

Ontario. 2019. Inquest into the Death of Kyle Knox Announced. January 21. https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/50988/inquest-into-the-death-of-kyle-knox-announced

Reynolds, Cynthia, 2011. Kyle James Knox. Macleans, November 8. https://macleans.ca/society/kyle/james/knox/

Tsekouras, Phil. 2021. Man killed by falling window at York University: police. CP 24. June 28. https://www.cp24.com/news/man-killed-by-falling-window-at-york-university-police-1.5488494?cache=%2F7.427985