Seneca College, or Seneca Polytechnic College as it is now called, is a non-York University entity that set up a branch on the Keele Campus in 1999. It stands out as the perhaps most visible sign of an Indigenous presence on campus. The College’s building on campus, by its sheer name, denotes an Indigenous presence, the College bearing the name of the Seneca, one of the groups of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and Six Nations of the Grand River (Mohawk, Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga, Tuscarora, and Seneca). The Seneca briefly occupied a couple of villages at the mouths of the Humber and Rouge Rivers in the late 17th century before they were pushed out by the Anishinaabe. The persistent Haudenosaunee presence in the province was realized with the Haldimand Treaty of 1784, when the British awarded them land six miles deep on each side of the Grand River in gratitude for their support of the King in the American War of Independence.

The western gateway entrance to the courtyard of Seneca College at York. It was adopted by the architects to pay tribute to the Senecas as the guardians of the Western Gate.

When I researched the Indigenous presence at Seneca College on the York Campus some years ago, I found that parts of the lands of York University are implicated in the Treaty as belonging to Six Nations. I also found out that Moriyama and Teshima, the architectural firm who drew the plans for the campus, did pay attention to the Seneca’s presence in the campus design: the entrance to the courtyard of the College is located in the west, on Ian MacDonald Blvd south of Fine Arts Road. This points to the Senecas’ westernmost position in the Haudenosaunee Confederacy in their traditional homelands in what is now New York State, where they still live as the Seneca Nation of Indians. The only other sign of the Seneca I found was in a set of organization and framed concept drawings sitting on one of the walls in the halls of the building done by Moriyama and Teshima. On them, there is a stylized S in the shape of an arrow that links the College to the Seneca. At some stage, however, the College shed the image, likely an initiative to protect the College from charges of cultural appropriation. The College has similarly buried a set of feathered bonnets that College administrators wore on special occasions.

The stylized arrow representing Seneca College. The upward thrust of the arrow depicts technology and the trailing end the artistic interpretation of the applied arts. The use of the symbol was abandoned around 2000.

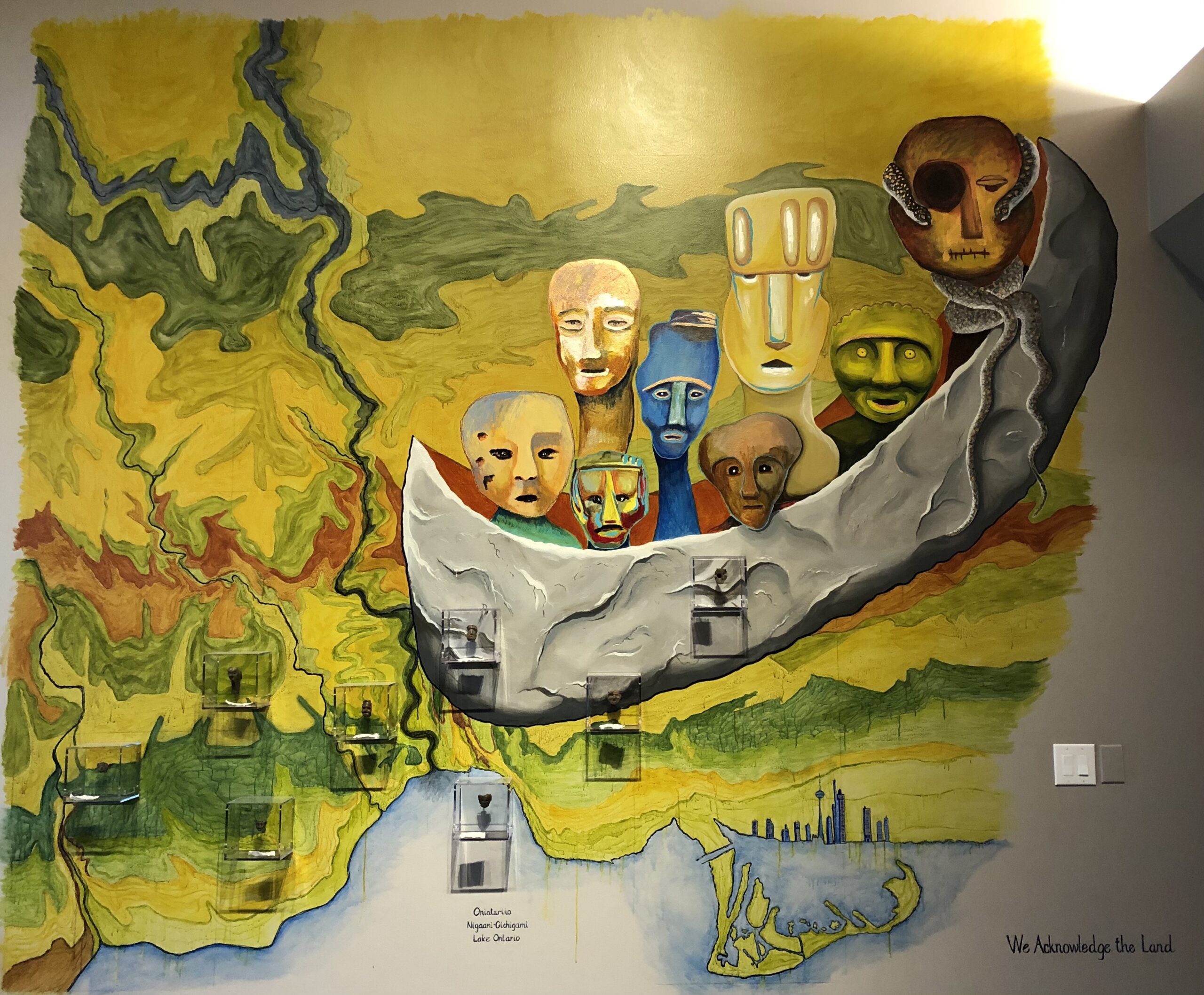

But when I led a Jane’s Tour on May 3, 2024, I was surprised to find something novel and quite spectacular in the Seneca College’s Courtyard, a mural named The Petition to the Water Spirits by Anishinaabe artist Isaac Murdoch from the Fish Clan of the Serpent River First Nation. Previous to the mural, I had only found three framed prints of Anishinaabe artists in one of the corridors.

It is this mural that prompted me to write this piece of a journey where I recall and connect a series of encounters and recollections related to water’s assertion and connection to Indigenous people on campus (and beyond). Murdoch’s mural is my first stop. The College put it up on the National Day of Truth and Reconciliation on September 21, 2023. The mural shows a warrior in a canoe, with his dog, launching a spear at a sea serpent with two trees flanking the scene and three fishes at the base. But one source also recounts that Murdoch’s inspiration for the mural came from the time when he, as a five-year old, and his siblings were separated from their mother and placed in a residential school. His own statement elaborates these points:

“For years, the Indigenous communities made petitions and offerings to the water spirits as part of the agreements between the people and the lands. When the newcomers came, this agreement was disrupted. It is said that an Indigenous man went to tell the newcomers of their obligations to make such offerings in order to not further upset the water spirits, but the newcomers did not respond. In fact, the newcomers took more from the land (resources) and even more devastatingly, took the children from the land (residential schools).

The Petition to the Water Spirits is a reminder of the offerings and obligations we have to the land we inhabit and to the children we have removed from their homes. It is a visual petition to return the land to what it was and to return the children to their homes. It is a reminder to offer respect that the water spirits deserve as a petition to get our children back.”

Isaac Murdoch’s mural The Petition of the Water Spirits

It was especially inspiring for me to confront Murdoch’s mural because I show one of his YouTube videos on water to my students. In it, he talks about water as “our first teacher,” how animals are the leaders and not people, and how the Anishinaabe are mere guests on Earth. His message to humans is for them to adopt an approach of humility and humbleness in the face of the more-than-human world. Murdoch also references Natural Laws that everybody across the earth understood at one time, laws that are still understood by the animals, but forgotten by people.

Murdoch’s mural is a reminder that water is also important to the Seneca, in the shape of the Grand River, and a collective key ally for all the traditional holders of the York University campus lands in the Humber River and Black Creek watersheds. These watersheds contain the Toronto Carrying Place Trail, the path used by Indigenous people and fur traders along the Humber River from Lake Ontario to Lake Simcoe. The riverbanks also harbour Indigenous villages and Three Sisters farm fields, containing corn, squash and beans, primarily of the Huron-Wendat. One of these Ancestral Huron-Wendat villages is located south of the campus. It was here that the Ancestors of the Huron-Wendat cultivated farm fields that extended to large parts of the present campus, including the land of the building where my office is located. The Ancestors also gathered water and caught fish in Black Creek which skirts the campus.

But meeting Murdoch at Seneca College was for me also a reminder of a very personal exchange. Only a few days before I discovered the mural, Wyandott multidisciplinary artist and utrihǫt Catherine Tàmmaro, whose Ancestors inhabited the Indigenous village just south of the campus, gifted me one of Murdoch’s prints, Water is Life. And only a few months earlier, Catherine spent a day at York University giving an arts workshop on painting using mud and water from Black Creek, part of a program titled Black Creek Walks, Talks and Dances organized by Lost Rivers and York University. On that occasion I gifted her a hand-woven blue-coloured linen table runner made by my late Aunt Anna-Britta. I wasn’t thinking about the symbolism of the gift, but Catherine reminded me that it, being blue like water and long and narrow like a river, represents running water.

Isaac Murdoch’s print Water is Life gifted to the author by utrihǫt Catherine Tàmmaro

Catherine’s connection to water is strong. On her website, she honours water in the Moon Water Song.

But the personal connections do not end here. A few years ago, I co-edited a book, Methodological Challenges in Nature-Culture and Environmental History Research, with Jocelyn Thorpe and Stephanie Rutherford, two former doctoral students here at York University but now professors at the University of Manitoba and Trent University, respectively. There are several chapters in it that I use regularly in my teaching. In one of them, Lianne Leddy, an environmental historian and member of the Serpent River First River, writes about the concept of dibaajimowinan as method, a way of paying respect and telling stories from Indigenous rather than conventional Western-based historical perspectives. In another chapter, Anishinaabe scholar Aimée Craft illustrates the use of dibaajimowinan with the words nibi inaakonigewin, an Indigenous expression referring to something resembling water management, nibi translating into water, but inaakonigewin being something much more complicated, a form of Anishinaabe law, where water is treated like “an actor in a relationship” that is as much manager as managed.

My journey continues. This time it leads me north from York University in the Humber River watershed to the McMichael Gallery, originally established to house the life work of the Group of Seven. There is now an extensive literature on the way the Group promoted the erasure of Indigenous people in their work, an erasure the Gallery is seeking to make up for by actively promoting a collection and exhibit of Indigenous art and establishing a connection to the local landscape. This is now illustrated by the work of Anishinaabe artist and scholar Bonnie Devine, another member of the Serpent River First Nation, and her mural project From Water to Water: A Way Through the Trees, which celebrates the Toronto Carrying Place Trail. As the centrepiece of her artwork, Devine is using effigy pipes from a nearby Huron-Wendat ossuary (burial site). The permission to use the pipes involved a unique deliberation between Devine and the Huron-Wendat Nation, support from the Gallery, and advice from the Gallery Ojibwe Elder Shelley Charles, Mariah Meawasige of the Serpent River First Nation, Dominic Ste-Marie of the Wolf Clan of the Huron-Wendat Nation, and utrihǫt Tàmmaro. Though led and executed by Devine, the project is unique in that it brought together the Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee and the Huron Wendat in a deliberate effort.

Anishinaabe artist Bonnie Devine’s mural From Water to Water: A Way Through the Trees at the McMichael Gallery

My travels continue yet again. This time I am travelling with Catherine to the Mnjikaning fish weirs at the narrows between Lakes Simcoe and Couchiching. It was here that the Wendat people and then the Anishinaabe gathered to harvest fish in the spring. The fish constituted a welcome source of fresh nutrition at the end of a long winter with often a monotonous dietary regiment. Catherine leaves some tobacco wrapped up in little red pouches at the site to honour the Ancestors.

Local places can amaze, there are stories and lessons to be learnt all around you. The meeting of people (humans and non-humans) in such places, I believe, are more than coincidental. I think it speaks to the concept of “all my relations,” the notion that all humans and more-than-humans are connected, and that those connections extend beyond time where past, present, and future generations are part of one unified whole. This becomes particularly relevant as I attend a discussion on sand with York University curator Clara Halpern and artists/scholars Cree Kai Recollet and Shannon Garden-Smith. In the conversation, Recollet refers to sand as a “sediment mineral kin” and Garden-Smith speaks about moving with sand as a way to imagine different futures, perhaps in the same way I am moving with water in this reflection. Sand and water are intricately related. Sand is formed by rocks travelling down rivers, streams and creeks and breaking down on the way. Sand is also formed under solid water, ice, and it may be that my name, Sandberg, mountain of sand, is derived from one of the many eskers, moraines, and drumlins that are part of the glaciated landscape in which I was born and raised.

Tracks and traces and changes (Sand Prints) by Shannon Garden-Smith, Vitrines Exhibition, York University Art Gallery. Note the red pouches with sand left by participants at the launch of the exhibition, an initiative led by Kai Recollet.

This is how far my mind extends in this journey of reflections, a journey that will likely look a little different tomorrow. It reminds us that York University and Toronto are not confined geographically and temporally. They are intricately connected with other spaces, times and peoples, both the human and more-than-human kind.

On August 20, 2024, I was engaged to do an Alternative Campus Tour for newly appointed faculty members at York. I was excited to do it. I felt I had a new tour instructed and guided by Murdoch’s Petition to the Water Spirits, featuring water as a central feature of an Indigenous presence but also with its own will and agency connecting me to various Indigenous spots on and off the campus. I imagined myself standing in the Seneca at York courtyard, water surrounding me in so many ways, looking at Murdoch’s mural, enveloped in a forecasted light rain, the College name referencing the Seneca and Haudenosaunee, the artist of the mural being Anishinaabe, me standing in or close to a former Three Sisters farm field of the Ancestral Huron-Wendat, and feeling the presence of the Toronto Carrying Place.

But there is one disappointment to this image. On the morning of the very day of my tour, Seneca College removed Murdoch’s mural because it was considered too damaged to remain or be repaired. It struck me in the moment that I might be able to save some remnants of it, but when I spoke to one of the workmen who did the removal he pointed out they were all rolled up in a sticky ball in his office in Markham. I didn’t push the issue. In the College’s official announcements on the removal of the mural, it states that “Seneca will preserve the work in another form on campus.” But when I enquired about the timing, Mark Solomon of the College informed me that the dream of making a mural series (of which Murdoch’s piece was to be a part) has died because of the “fiscal situation.” And as for the Murdoch mural itself, he regrets that the plans to frame a picture of the mural “has not happened” because “all that is happening.” Perhaps it will, like water often does, reappear again one day. For me the mural will always remain and I will continue to take people there and speak about it on my tours. I did so on a tour for the Robarts Centre for Canadian Studies at York on April 10, 2025. The tour participants inspired me to finish and post this reflection. Thank you.