This safety phone in Central Square is one of the 35 emergency phones located on campus. The bright yellow colour and spinning blue light are supposed to make these phones easy to see…but how often do we look up from the phones in our own hands as we walk across campus? And if we wanted to call for help or sound an alarm, wouldn’t we just use the York U Safety app for that?

In many ways, these phones are symbols of changing technologies and changing conversations. They stand for what has been the dominant conversation about safety on campus for decades: a conversation where, when we talk about promoting “safety”, we know what’s really meant is “avoiding sexual assault”. This is a story that we have to think about more closely.

But before I talk about the very real and very serious issue of sexual violence on college and university campuses, including York’s, let’s take a moment to talk about it more generally. Accurate statistics around sexual assault are hard to find, because, according to Statistics Canada, 91% of these crimes are not reported to police. And the Canadian Federation of Students provides some more disturbing figures:

- 86% of victims of sexual violence are women.

- Over half of Canadian women have experienced at least one incident of sexual or physical violence. Of these women, 60% have experienced more than one.

- Women aged 15-24 experience the highest rates of sexual violence.

- 80% of female undergraduates surveyed had been victims of violence in a dating relationship.

- In a recent survey, 60% of Canadian college-aged males said they would commit sexual assault if they were sure they could get away with it.

Conversations about sexual assault, especially those in the media, continue to focus on “stranger danger” instead of questioning the dominant stories we tell about sexual violence, and the culture we live in that makes this violence possible. Even though roughly 75% of sexual assaults are perpetrated by someone the victim knows – intimate partners, family members, friends, neighbours – and 80% take place in her own home, we continue to talk about technologies such as safety phones as things that will help to prevent sexual assault, even though they’d be no help at all in most cases.

We also keep telling stories that focus on what women should and should not do to keep safe. Women are taught a seemingly endless list of “don’ts” – don’t walk alone, definitely don’t walk alone at night, don’t drink too much, don’t wear that, don’t be “promiscuous”…basically, don’t do anything that can possibly be seen as being a “slut” or “asking for it”…because if a woman breaks any of these rules, and she is assaulted, then it’s her own fault, and she got what she deserved. This kind of thinking is what’s known as “victim blaming”, and it happens all the time – including here at York.

Hiring more personnel and putting the responsibility on students to make the “call” to protect themselves against sexual violence is the dominant conversation around safety and security issues on university campuses.

This photo of the York University safety app says a lot about York’s priorities and understandings of safety. The app puts the onus on students to protect themselves rather than addressing the rape culture that is responsible for security issues in the first place.

From this particular safety phone, you can see Osgoode Hall, where, on January 24, 2011, at a meeting to address the safety concerns of women at York, a Toronto police officer told women they could avoid being assaulted by not dressing like “sluts”. This comment became a flashpoint and inspired a group of Toronto women to hold a march on April 3rd, 2011. They called it “SlutWalk”, and it has since grown into a transnational movement, with tens of thousands of women (and allies) in North America, Europe, Asia, and South America taking to the streets to protest victim blaming and rape culture.

Osgoode Hall Law School, where Toronto Police Constable Michael Sanguinetti told a group of York students at a campus safety information session that “women should avoid dressing like sluts in order not to be victimized”. This comment inspired four local women to organize a march on Police Headquarters. This march was the first Slutwalk, and, according to organizer Sonya Barnett, one of its key demands was for “Police Services to truly get behind the idea that victim-blaming, slut-shaming, and sexual profiling are never acceptable”. Yet the Slutwalk has also been criticized as being a very white movement that glosses over the concerns of racialized women, to the point where one of the original founders resigned over it.

In the inaugural “Slutwalk”, thousands of Torontonians took to the streets to protest victim blaming and rape culture. Similar marches have since taken place all over the world.

Rape culture is when sexual violence is portrayed as something that’s inevitable, with the responsibility placed on women to do the right things not to be assaulted, because assaults are going to happen…instead of putting the responsibility on rapists not to rape.

This phone also symbolizes the disconnection between what kind of help and support victims of sexual violence are supposed to receive…and what actually happens when the police and courts become involved. The reality is that, no matter how “sympathetic” a victim, most cases don’t proceed to trial, conviction rates are extremely low, and sentences are the second lightest of any violent crime. Even if a woman who had been assaulted used this phone to call police, there’s no guarantee she would receive any kind of justice…or be treated with respect…or even be believed.

Another story that can be told about this safety phone is how York, worried about bad press and declining enrolment, has spent tens of millions of dollars on security in an effort to improve their image. But do technologies that don’t address the root causes of violence (including sexual violence) really make us safer? Or do they just make us feel safer?

Security guards, safety phones, smartphone apps, and CCTV cameras are all designed to create an image of safety. But in many ways they continue to play into the dominant media narrative of York as a particularly “dangerous” place because it is located near Jane and Finch, a place the media and police have been equating with violent crime for years. This perception of York has become so widespread that it will probably surprise you to hear that, actually, the downtown neighbourhood which includes U of T has a way higher incidence of reported sexual assaults, ranking 2nd out of 140 Toronto neighbourhoods (to Ryerson’s 11th and York’s 19th)…because that doesn’t fit with the stories you’ve come to know and expect.

Yet another technological fix to tackle what is, in fact, a much deeper rape culture that prevails on campuses.

So while it’s meant to be a symbol of the efforts that York is taking to prevent sexual violence on campus, this safety phone also symbolizes the conversations we aren’t having…or at least aren’t having loudly enough: the ones that call out victim blaming; the ones that talk about power, and who has it, and how it’s used; and the ones that name how sexism and racism and homophobia and transphobia and ableism intersect with sexual violence.

But could this safety phone be reframed to tell a more hopeful story? Could it be used as a symbol to inspire students and administrators and the media to shift the conversation around sexual violence on campuses?

Rape culture is not something that’s unique to York. Just to name a few well-publicized incidents, in the past year, UBC and St. Mary’s University made headlines when video of Frosh Week chants containing rape jokes appeared online, Ottawa U suspended its men’s hockey team after multiple players were involved in a sexual assault after an away game, and male students at Dalhousie’s Dentistry School were exposed as having made a Facebook group that “joked” about, among other things, sedating their female classmates to sexually assault them. And there are many, many more examples at universities and high schools across Canada and the US, like Emma Sulkowicz’s Carry the Weight Project and the film The Hunting Grounds, so it seems obvious there are important conversations to be had.

Many groups on campus have organized, written, and pushed for both a more direct and a more intersectional approach to addressing sexual violence.

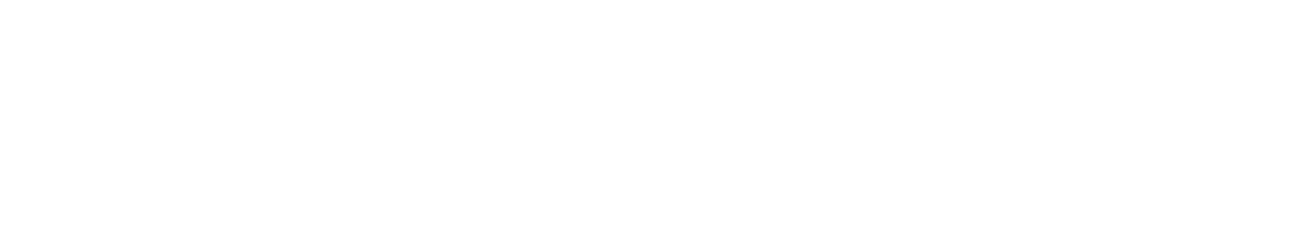

This cartoon was created by York students Jane Kim, Shayna Lauer, and Helén Marton as a group project for a 2013 Design For Public Awareness class. As Marton explained in the May 20, 2013 Toronto Star, "We wanted to use the power in these heroes to comment on how people view sexual violence".

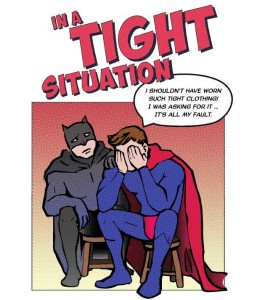

A student uses the York's "This is my time" slogan to challenge the University to stand with survivors and end rape culture on campus.

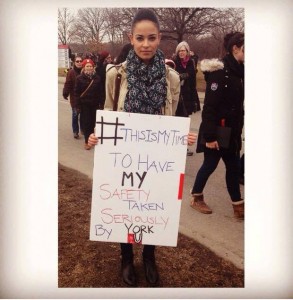

Commissioned by the Art Gallery of York University, Chase Joynt’s IMAGINE US coopts and displays the structures of various York University advertisements and posters in densely populated public spaces to call attention to sexual and gender based violence on campus.

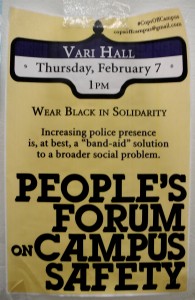

Students debate the underlying social justice issues surrounding campus “safety” in Vari Hall; just one of many grassroots efforts to address the root causes of violence on campus.

And perhaps, some progress is even being made at the official level of the university. The University’s Centre for Human Rights has spearheaded some efforts, such as the REDI tutorial, which stands for respect, equity, diversity, and inclusivity. Further, in February, 2015, York University released an official policy on Sexual Assault Awareness, Prevention, and Response. This policy recognizes that:

“Sexual assault is a serious and systemic issue that impacts the individual, community, and society in general. Sexual assault is a traumatic experience that violates the sexual integrity, personal boundaries, trust and feelings of safety of the individual and can have significant long lasting physical, emotional, and psychological impacts on a survivor. Anyone can experience sexual assault. However, individuals may encounter increased vulnerabilities based on their identity or perceived identity including such factors as race, economic status, gender, gender expression, sexual orientation, language, physical or mental ability, and/or immigration status. Every survivor reacts differently to their experience. Survivors experience many barriers to disclosing, reporting, and/or seeking support; barriers can differ based on the lived experience of the survivor. York University affirms its ongoing commitment to foster a culture where sexual assault and its impact are understood, survivors are supported, and those who commit incidents of sexual assault are held accountable.”

Although this is a step in the right direction, it is clear that much more progress needs to be made, and that policies have to be put into practice.

At its most basic level, a telephone symbolizes engaging in dialogue and making connections. And more and more, people are starting to talk about sexual violence as something that’s embedded in our culture, something that’s normalized, condoned, excused, tolerated, permitted, joked about…and inevitable.

But sexual violence is not inevitable. And, more and more, conversations are shifting. “Active consent” laws are being passed, where consent is defined as an enthusiastic “yes” instead of the absence of a verbal “no”. Students are standing up to college and university administrations, demanding they fulfill their legal and moral obligations to students who have been assaulted. More and more, news stories about rape culture are not asking whether or not it exists, but what can be done to combat it.

So what if this safety phone could be reframed as a reminder that conversations around rape culture and active consent need to be ongoing? That these conversations aren’t unique to any one campus…or even to campuses at all? That silence is violence? That resources could be redirected to education instead of security? That instead of putting the onus on individuals to do the “right” things to NOT be assaulted, we could foster an environment where what people are taught is the only thing that will actually stop sexual violence – which is not to commit it.

If these are the kinds of conversations we have and keep having, there is hope that one day the need for such a phone will be as obsolete as the technology itself.

So I ask you, having heard this story, to think about what kinds of stories about safety and sexual violence you see and hear in the world around you: in the media you consume; in the technologies you use; in the ways public spaces are laid out, and how you move through them; and how they make you think about being “safe” in physical and virtual environments? How do they shape the conversations that you have? And what other kinds of conversations and stories could they make possible?

References:

Canadian Federation of Studients – Ontario, 2013. Factsheet: Sexual Violence on Campuses. Accessed 3 June 2015 at http://cfsontario.ca/downloads/CFS_factsheet_antiviolence.pdf

Ikeda, Naoko and Emily Rosser, 2009/2010. “’You be Vigilant! Don’t Rape!’ Reclaiming Space and Security at York University.” Canadian Woman Studies, 28, 1 (Fall/Winter), 37-43.

Statistics Canada, 2015. Trends in Sexual Offences. Accessed 10 June 2015 at http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85f0033m/2008019/findings-resultats/trends-tendances-eng.htm

York University. Sexual Assault Awareness, Prevention, and Response Policy. Accessed 3 June 2015 at http://safety.yorku.ca/prevention-response-sexual-violence/

Biography:

Michaela McMahon is doctoral candidate in the Faculty of Environmental Studies. She believes you.