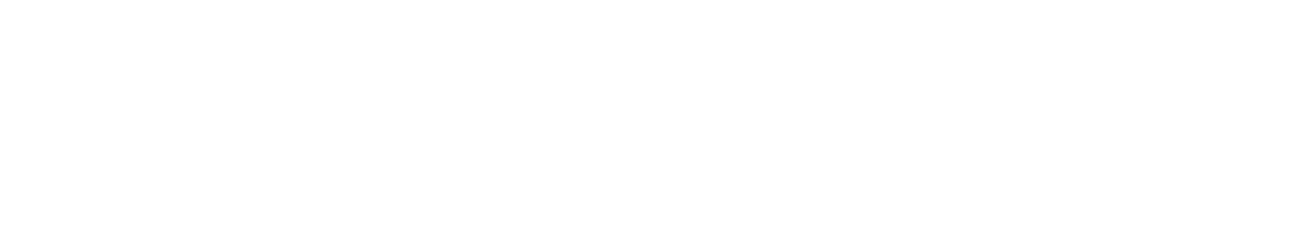

The presence of wheelchair ramps in buildings is often seen as a sign of progress towards a more accessible future where persons with disabilities are included in the design of buildings and public access spaces. This argument can be made with regard to the wheelchair ramp that is located at the north end of Curtis Lecture Halls in front of the Campus Walk that crosses the campus.

Curtis Lecture Halls wheelchair ramp at 125 Campus Walk

In this short essay, I will argue that we can in fact do a lot better in meeting the needs of disabled bodies. This does not only apply to the building of ramps, but also the way we name buildings and paths. I here ask why do we have a need for ramps at all? I also argue that the Curtis Lecture Halls ramp and its surrounding area are symptomatic of ableism, the process where disabled bodies appear as afterthoughts or even overlooked in planning the University and in the construction and naming process of buildings and public spaces.

The naming of the pathway adjacent to the wheelchair ramp provides another example of an ableist discourse. It is called “Campus Walk,” a colloquially adopted name which carries assumptions about the type of people who use this part of campus. The term “Campus Walk” implies a level of upright, bipedal, forward momentum which completely excludes individuals in wheelchairs, individuals using crutches, people with walkers or canes, people on mobility scooters or other disability vehicles. It is exclusionary and ableist, and it socially others toponyms, such as Campus Roll or Campus Hobble, that could reference the unique modes of individual movement of disabled bodies.

Another aspect that feeds into the inherent inaccessibility of this wheelchair ramp pertains to the actual history of wheelchair ramps themselves. The first evidence of ramps being used originates in ancient Greece where they were used as a means to harness the power of gravity to move ships and large masses of materials (MedPlus, 2019). In the early 1900s, ramps were rethought to help travellers arriving into Grand Central Station move their luggage more efficiently and quickly (MedPlus, 2019). It wasn’t until after World War II when a great number of veterans globally returned home from war with mobility related injuries that a need for wheelchair ramps in modern infrastructure was recognized more widely (MedPlus, 2019). But despite the eventual recognition of a need for disability accessibility in modern infrastructure, the wheelchair ramp is intrinsically ableist because of its origins as a luggage, equipment, and machinery transportation aid. This evolution of the ramp carries forth the narrative that disabled persons are of the same value and are seen socially in the same light as pieces of equipment, machinery, and inanimate objects that need to be moved from point A to point B with ease. Having this mindset of disabled people automatically inserts them into the public’s zeitgeist as secondary to able-bodied people. Thus, any infrastructural features created to be more accessible to disabled persons, specifically wheelchair ramps, are included as retrofitted add-ons as opposed to being included in the original blueprints of a building.

If buildings, public-access infrastructure, and social gathering places were genuinely created with disabled persons in mind, why would we even have a need for ramps? Could we not simply make the ground more level so that all people could enter and exit with ease? The need for wheelchair ramps in the first place embeds a sense of social hierarchy or superiority of able bodied over disabled people and therefore accommodations must be made in order to allow members of the disabled community to fully participate and engage with the world around them. Without these “accommodations” many members of the disabled community would be unable to work, go to school, be independent, or feel safe to live and exist in their bodies as they contrast with the world around them.

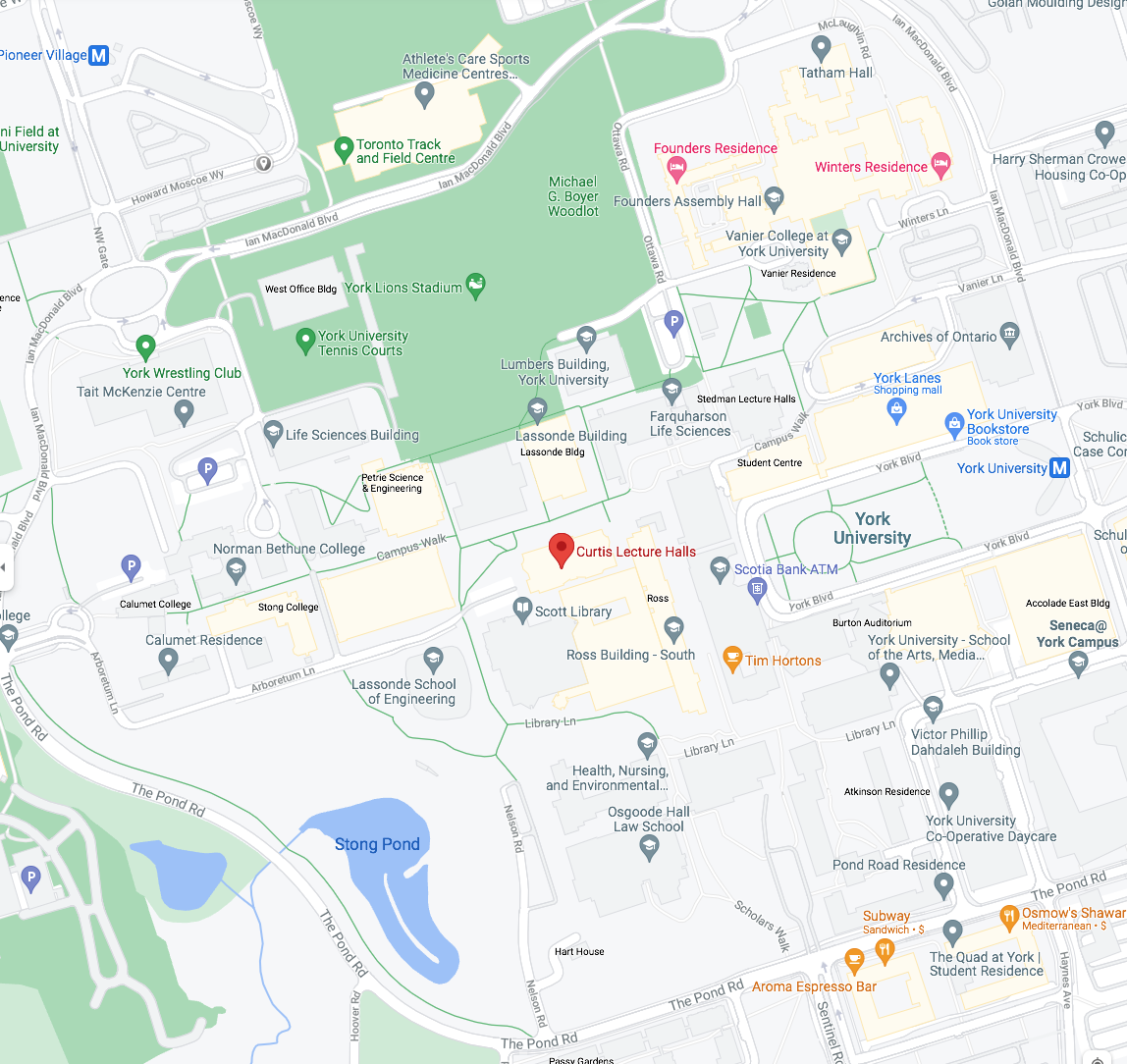

Unfortunately, the problems with wheelchair ramps doesn’t stop at their history as pertaining to the movement and transport of machines, luggage, and other goods. When wheelchair ramps are not well maintained, they can become hazardous to the members of society who rely on them the most. Specifically, issues can arise when ice is inadequately cleared, when the rails are not cleaned of rust frequently, the concrete is not maintained and smoothed on a regular basis, and the automatic door openers are frequently out of order. Through simple acts of neglect in maintenance or a de-prioritization of disabled bodies through the concurrent de-prioritization of maintenance or upkeep of wheelchair ramps, the dominant social narrative becomes automatically and unconsciously embedded with the normalized notion that disabled bodies can be an afterthought.

One poorly maintained wheelchair ramp along Campus Walk

When this photo was taken on December 16, 2021, the automatic door opener at the wheelchair ramp at Curtis Lecture Halls was out of order, a not uncommon occurrence for other similar doors on campus.

It is my proposition that moving forward, building plans and public access spaces start to implement a single type of entrance way, either in the form of ground level entrance ways, or just a slope/ ramp. When buildings have a one-size fits all entrance-way or pathway that is accessible both to the disabled community as well as the able bodied community, they are guaranteed to be much better maintained since everyone is required to use it, and not just a single, already marginalized demographic.

The south entrance to Central Square is at the same level for disabled and abled bodies. Unfortunately, on this day, 16 December, 2021, the automatic door did not work properly.

The system of both stairs and ramps perpetuates a hierarchy in society. On top are those individuals who can readily participate in any and all societal functions that they so choose. At the bottom are individuals who must have room made for them and accommodations put in place in order for them to fully participate in society. This is in contrast to a system where the needs of both groups are available as a standard function of architectural design. It is important that campus community is made aware of the way inaccessibility is normalized through disabled bodies being frequently considered as an afterthought.

References

Canada's Aviation Hall of Fame. (2021, May 25). Wilfred Austin Curtis - Canada's Aviation Hall of Fame. Canada's Aviation Hall of Fame -. Retrieved November 4, 2021, from https://cahf.ca/wilfred-austin-curtis/.

Hamraie, Aimi (2019). Making Access Critical: Disability, Race, and Gender in Environmental Design. Retrieved December 16, 2012, from https://www.vanderbilt.edu/mhs/person/aimi-hamraie/

MedPlus. (2019, November 15). The history of the wheelchair ramps. MedPlus. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from https://www.medplushealth.ca/blog/the-history-of-the-wheelchair-ramps/#:~:text=and%20mobility%20issues.-,The%20History%20Of%20The%20Wheelchair%20Ramp,most%20famous%20structures%20in%20history.&text=The%20ancient%20Greeks%20constructed%20a,across%20the%20Isthmus%20of%20Corinth.

Scalar.usc.edu. (2018). Curtis Lecture halls. A Concrete Vision: Brutalist Architecture at York University. Retrieved November 4, 2021, from https://scalar.usc.edu/works/a-concrete-vision-brutalist-architecture-at-york-university/curtis-lecture-hall.

Biography

In 2017, I underwent the life changing health experience of a spinal surgery. Since then, I have endured regular doctors’ appointments, visits to emergency departments, lots of strong medication, and endless fights for accessibility within my daily life and in the medical system. Because of my personal experiences with inaccessibility and living in a disabled body, I want to do my part towards making the world a more accepting and accessible place for all people in all bodies. This essay I completed in Professor L. Anders Sandberg’s course ENVS 4750 The Political Ecology of Landscapes. I have also worked towards actualizing a solar charging station for electric disability mobility vehicles on the Keele Campus in Professor Jose Etcheverry’s course ENVS 4400 Renewable Energy Policies and Practices.