On a mid-morning Friday in late November, I was guiding a group of young Indigenous women from Saskatchewan to Ahqahizu (A-ka-hee-zu), the giant sculpture of an Inuk man who is playing soccer with a walrus head, that is positioned at the north end of the York Stadium. The visitors hailed from Treaty 6 territories – the traditional homeland of the Métis, Cree, Saulteaux, Blackfoot, Dene and Nakota Sioux. While they came from many different nations, they all now reside in what is known as inner-city Saskatoon and are part of a girls group called the Young Indigenous Women’s Utopia. As their name implies, they are a collective that imagines a world that is free from colonial- and gender-based violence. They were in Toronto to launch their new book - KÎYÂNAW OCÊPIHK – a collection of photographs, essays and conversations that reflect on their work and activism (Young Indigenous Women's Utopia, Young Indigenous Women's Utopia 2.0, & Mandamin, 2022). I had been asked by my colleague Sarah Flicker to do the walk and I was happy to oblige. We visited several sites but Ahqahizu spoke to me in particular and inspired me to write this piece.

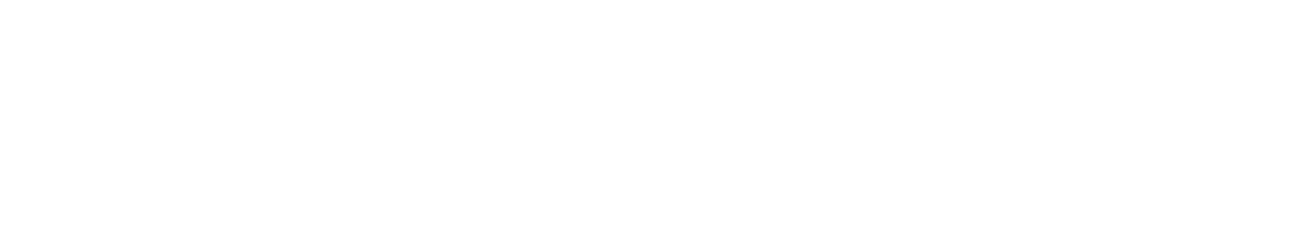

It was unseasonably warm at plus 7 degrees, but it was also windy. The young women were visibly cold so we hurried through the tour conveying the bare minimum but I can here afford to give a little more detail. Ruben Komangapik (from Pond Inlet) and Koomuatuk (Kuzy) Curley (from Cape Dorset) carved Ahqahizu from a 23-tonne piece of Stanstead granite; 8ft tall by 8ft wide shipped to Toronto, from a stone quarry in the Eastern Townships in Quebec. After carving away at its form, the finished piece stands at 15 tons. Komangapik and Curley were helped by a team of assistants and apprentices, including students from the Department of Visual Art and Art History and the local Jane and Finch neighbourhood who thereby picked up knowledge of Inuit culture and heritage. This was sometimes a challenge because the two sculptors did not work with any calibration tools or lines drawn on the rock. The pair spent about 200 days working on the piece.

Ahqahizu, the soccer player

We also talked about the symbolism of the sculpture. According to stories told in Nunavut, the soccer player is associated with the northern lights, or Aurora Borealis or Aqsarniit (aksarnek), meaning the trails of spirits or souls of deceased people playing soccer, waiting for their return to human form to play by the light of the moon on the frozen sea ice. Several girls told me they had seen the northern lights and one of them referenced its spiritual symbolism. The sculpture is very personal for Komangapik whose father Mikiseetee died of cancer before he embarked on the project and to whom the sculpture is dedicated.

Plaque providing information on Ahqahizu

The sculpture was unveiled on National Aboriginal Day June 21, 2016. It was a momentous and warm sunny day. The sculptors were there along with dignitaries from the University. The attendees were served seal meat, Arviat-raised singer Susan Aglukark sang her hit song O Siem, Iqaluit Matthew Nuqingaq performed a drum dance, and York University president Mamdouh Shoukri spoke of the sculpture fitting in with Toronto as a multicultural city and called the project one of many efforts to “Indigenize” the university campus. Ahqahizu was also on full display for athletes and spectators who attended the North American Indigenous Games which were hosted at York University in the summer of 2017.

The sculpture was commissioned by York University and the Mobilizing Inuit Cultural Heritage project, a $3.5 million multi-media, multi-platform research-creation collaboration between various art departments at York and supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and other organizations aimed at engaging and employing Inuit and non-Inuit community members and artists (Gray et al., 2022).

When I look a little further into some of the aspects of the northern lights, Inuit and walruses, I find out a few interesting things that I would have liked to talk to the young girls about. The hunting of walruses is an important activity in Inuit culture as it provides an essential source of food, fibers, hides, and tusks. Perhaps the use of the walrus head as a soccer ball, though perhaps seeming disrespectful from Western eyes, is part of the practise of using all parts of the animal in order to respect it fully.

Detail from Ahqahizu showing his foot kicking the walrus head

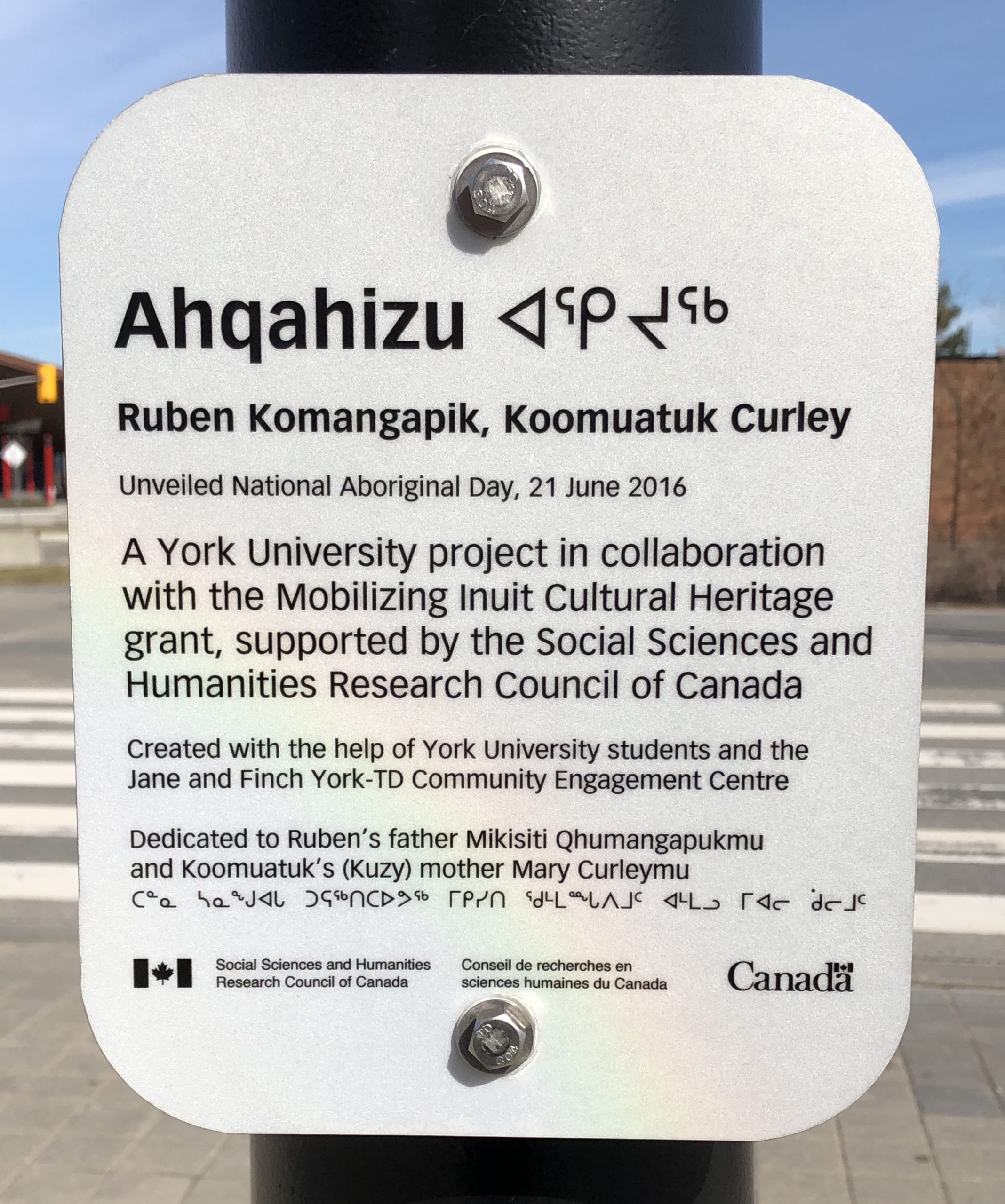

I also learn that there are lots of interpretations of the northern lights or the Aurora Borealis. For scientists, it is a phenomenon caused by particles from the sun interacting with different gases. The type of gases renders a specific shimmer and pattern to its display. In Scandinavia, the northern lights were once seen as dangerous, having the potential to set children’s hair on fire. But the Inuit prefer their own soccer story which can be used as a healing device. This is the case in Inuit writer Michael Arvaarluk Kusugak’s book Northern Lights: The Soccer Trails (1993). The book speaks to the collective pain, grief and intergenerational trauma experienced by the Inuit and the comfort that some may feel through the northern lights. The book features the story of a little girl, Kataujaq, and her close relationship to her mother. Her mother contracts an illness and is taken to a hospital in the south and never returns. Kataujag falls into a depression but is able to find solace when she and her grandmother watch the northern lights.

Book cover of Michael Kusugak's Northern Lights, The Soccer Trails

According to Kathleen Forrester and Judith Saltman (2016), Kusugak’s book emerged from a personal and community need to start talking about the youth suicide crisis in the North in the 1990s. The book addresses the profound impact of the northern tuberculosis epidemic of the 1950s when thousands of sick Inuit were moved to hospitals in the South where they often passed away without their families’ knowledge. This happened during the resettlement and residential school era of the 1950s and 1960s when Inuit communities suffered from a disintegration of family and community relationships that had impacts on future generations.

Forrester and Saltman feel the book serves as a culturally relevant “vehicle” to tackle the suicide epidemic amongst Inuit youth and its colonial legacy, “echoing the words of Sarah Ahmed that ‘the past lives in the very wounds that remain open in the present’.” They then conclude by connecting Kusugak’s story to a more general message, inviting readers:

… to also look to the night sky and “see someone special whom you thought had gone away forever,” … [T]hus we see on a very palpable level the political work of Kusugak’s writing—as he links the present with the past, he also encourages the reader to dismantle oppositional barriers in their own perception between objective reality and spiritual knowledge, between “new” and “old” ways of knowing and being. … Northern Lights … pushes against and ruptures the binary worldview of dominant empirical knowledge systems in order to open up regenerative possibilities for future generations.

This is what I would have liked to communicate to the young women I was guiding that day, that standing there at Aqhahizu, we could all have thought about somebody dear to us who had passed on, but who is still playing soccer in the sky, and still being connected to us.

There is another interesting wrinkle to the Aqhahizu story. In 2016, an undergraduate student, Megan Nowick-Rigelhof, in the Community Arts Program in the then Faculty of Environmental Studies conducted an art project, Stone Fragments. She invited participants to collect the leftover and discarded stone pieces from Ahqahizu and then to compose art pieces of their own. These compositions appeared in various parts of the campus, but especially in an area south of the Ross Building. Once the stones were placed on the ground, they became public art. There was the possibility that non-participants would take photos of the work and post them online, as I have done here. There was also the chance that non-participants would move the stone pieces. Indeed they did travel and all have now been re-moved completely by the university. This was all expected: it was part of the curatorial transformation process of the stone pieces taking on a new location, form and meaning through an exterior perspective. I managed to save a few pieces that now sit in my office. I sometimes touch them. There is a smooth cold touch to the stone pieces where the sculptors made their cuts, but there is also a rough side where they broke off from the larger block. They are awesome, I think, millions of years old, ancient relatives, the once habitat of Ahqahizu, and representative of the smooth ups and rough downs of the lives of us humans.

Stone Fragments invites an interesting, challenging and potentially liberating dimension. First, the art pieces, once done, became public art, that is, not owned by anybody, nor protected. Second, there was the possibility that the works of art would become changed, transformed or destroyed, or photographed from other purposes than the project (as they are below). The process challenges the notion of private property, permanency, and copyright, suggesting that such notions are not absolute and eternal. This is also the case with Indigenous property rights that differ in scope and extent from those of colonial property patterns.

Stone fragments discarded from the sculpting of Ahqahizu

One of the artworks from Stone Fragments

Another artwork from Stone Fragments

Professor Anna Hudson, the leader of the Mobilizing Inuit Cultural Heritage project at York University, says that the collaboration is part of a project that aims to center the Inuit voice on their creative works of art. The problem, she explains, is that many Inuit art works are in private hands. The goal, she says, is “creating opportunities where there is greater interaction and more knowledge and awareness of Inuit art as a vital presentation of Inuit culture” (Bonta, 2015).

In a recently published book, Hudson and her co-editors (Hudson et al., 2022) shed light on the potential role of the arts and culture in promoting sovereignty in the Circumpolar North. It is guardedly optimistic, noting how the arts and culture in the past may have been appropriated and dependent on southern tastes and mores, and not for the Indigenous people who inhabit the region. The current moment may be different, building a momentum for arts and culture to be part of and for the community, where “art is an archive, where “art is everything,” and where “curating is advocacy” in support of these trends.

Aqhahizu is surely a symbol of hope and friendship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, and an example to emulate for other groups. But it is perhaps regrettable that there are few manifestations of art by the Indigenous groups whose traditional lands compose the campus. Hopefully, Aqhahizu will inspire that to happen in the future.

References:

Bonta, B. (2015). Peaceful Societies: Walrus Skulls Used as Soccer Balls, September 3. https://peacefulsocieties.uncg.edu/2015/09/03/walrus-skulls-used-as-soccer-balls/

Forrester, K. and J. Saltman (2016). Felt Knowledge in Michael Kusugak’s Picture Books, Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature, 54, 1, 10-17.

Gray, B., L. Schwarzentruber, N. Stern, and A. Lawson (2022). Sananguaq: Inuit Stone Carving for Our Community, pp. 312-317. In Hudson, A., H. Igloliorte, and J.-E. Lundström, editors (2022). Oummut Oukiria! Art, Culture, and Sovereignty Across Inuit Nunaat and Sápmi: Mobilizing the Circumpolar North. Fredericton, NB: Goose Lane.

Hudson, A., H. Igloliorte, and J.-E. Lundström, editors (2022). Oummut Oukiria! Art, Culture, and Sovereignty Across Inuit Nunaat and Sápmi: Mobilizing the Circumpolar North. Fredericton, NB: Goose Lane.

Young Indigenous Women's Utopia, Young Indigenous Women's Utopia 2.0, & Mandamin, Z. (2022). KÎYÂNAW ocêpihk. Toronto, ON: McGill and York University.